苏东坡正月里下乡察民情

司马一民

王安石变法中的不少举措,招致朝廷中许多人的反对。苏轼、苏辙兄弟也在其中,两兄弟议论朝政得失直言不讳,得罪了王安石及“变法党”。熙宁三年(1070),苏辙被贬出京师为陈州学官,第二年熙宁四年(1071)四月,苏轼也被贬出京师为杭州通判,十一月到任杭州。

熙宁六年(1073)正月,苏轼(号东坡居士,世称苏东坡)奉命去富阳、新城、于潜“视政”。所谓“视政”,也就是巡查,看看下属县民生和官员吏治的情况,这是通判的分内之事。没有史料告诉我们当时苏东坡在富阳、新城、于潜巡查的情形,不过,好在苏东坡有及时写诗的习惯,他此行写了多首诗纪事,我们可以略知苏东坡此行的一二。

新城即新登。新登位于杭州市西南部,西南连接胥口镇,与桐庐、临安接壤,是杭州市富阳区西部的商贸中心。三国孙吴黄武五年(226)析富春部分县地置新城县,为新登建县之始。五代十国时期后梁开平元年(907)为避太祖父朱诚讳,改新城为新登。北宋太平兴国三年(978)复改富春为富阳,后一年又改新登为新城。南宋建炎三年(1129),以杭州为行在所,富阳、新城两县隶临安府,后世县辖屡有变更。

我们先来读苏东坡此行写的第一首诗《往富阳、新城,李节推先行三日,留风水洞见待》:

春山磔磔鸣春禽,此间不可无我吟。路长漫漫傍江浦,此间不可无君语。金鲫池边不见君,追君直过定山村。路人皆言君未远,骑马少年清且婉。风岩水穴旧闻名,只隔山溪夜不行。溪桥晓溜浮梅萼,知君系马岩花落。出城三日尚逶迟,妻孥怪骂归何时。世上小儿夸急走,如君相待今安有?

李节推名佖,当时为杭州节度推官。风水洞,据《杭州图经》载,距钱塘旧治五十里,在杨村慈岩院。洞极大,流水不竭,清风微出,故而名为风水洞。苏东坡奉命出巡富阳、新城,李佖比苏东坡早出杭州城三日,在风水洞等候苏东坡,显得对苏东坡很恭敬,苏东坡写了此诗作谢。

全诗写景写行,读来轻快,显出苏东坡的心情很好。最后两句“世上小儿夸急走,如君相待今安有”,字面意思是,这世上小孩儿都以急速奔跑为好,现如今像您这样早早地出城等待同伴的人哪里有啊。似乎在夸奖李佖的稳健。不过,这两句诗日后却成了苏东坡“谤讪新政”的罪证之一,“世上小儿”是指那些推行新法的“新进勇锐之士”。苏东坡自己也在《乌台诗案》说:“熙宁六年正月二十七日游风水洞,有本州推官李佖知轼到来,在彼等候。轼到乃题诗于壁,其卒章不合云‘世上小儿夸疾走’,以讥世之小人多务急进也。”可见苏东坡虽然已经离开了京师朝廷,还是忘不了那里的是是非非。不过,这不是他与王安石个人之间的恩怨,两人忠君报国的出发点一致,只是政见不同罢了。

接下来我们读《新城道中二首》:

其一

东风知我欲山行,

吹断檐间积雨声。

岭上晴云披絮帽,

树头初日挂铜钲。

野桃含笑竹篱短,

溪柳自摇沙水清。

西崦人家应最乐,

煮芹烧笋饷春耕。

其二

身世悠悠我此行,

溪边委辔听溪声。

散材畏见搜林斧,

疲马思闻卷旆钲。

细雨足时茶户喜,

乱山深处长官清。

人间岐路知多少,

试向桑田问耦耕。

这两首诗的大致意思是这样的——

其一:东风知道我要去山里,吹停了连日不断的雨。岭上的云朵像戴着棉帽,旭日初升如同铜钲挂在树梢。低矮的竹篱旁桃花朝我点头含笑,沙溪边柳条像是对我轻舞。居住在西山一带的人家很快乐,煮葵烧笋犒赏辛苦的春耕人。

其二:人生之路如同我现在行路,牵着马慢悠悠行走在溪边。朝廷上的党争,有用之材也怕搜林之斧,疲惫的战马希望听到鸣金收兵。茶农为细雨绵绵而高兴,在这大山深处有我的好友做着清官。人间的歧路有多少?去问问田里耕作的农民吧。

在去往新城途中,眼前明媚秀丽的春光和农家的春耕景象,使苏东坡心情舒畅。似乎连大自然都格外偏爱这位外乡人,为他的出行,“吹断檐间积雨声”,野桃“含笑”点头,“溪柳”翩翩起舞;“西崦人家”快乐耕作,细雨润茶喜上眉梢,简直就是桃花源里。

在《新城道中二首》的字里行间,我们看到了一位放飞心情的快乐的苏东坡。

苏东坡去富阳、新登“视政”以后,紧接着又去了于潜“视政”。虽然正史上没有记载苏东坡这次于潜“视政”的具体内容,但是苏东坡留下了三首诗,姑且算“视政”笔记吧。从中,我们可以知道苏东坡在于潜的一些行踪。

第一首诗告诉我们苏东坡考察了于潜官员的政绩。于潜县令刁铸与苏东坡同一科考中进士,称为同年。看来考察之后苏东坡对这位同年的政绩是满意的,要不然,以苏东坡的性格和为人,是不可能仅仅因为同年就给予好评的。我们读他写的这首《于潜令刁同年野翁亭》,可以看出他对于潜县令刁铸的好评:

山翁不出山,溪翁长在溪(自注:前二令作二翁亭)。不如野翁来往溪山间,上友麋鹿下凫鹥,问翁何所乐,三年不去烦推挤。翁言此间亦有乐,非丝非竹非蛾眉。山人醉后铁冠落,溪女笑时银栉低。我来观政问风谣,皆云吠犬足生牦。但恐此翁一旦舍此去,长使山人索寞溪女啼(自注:天目山唐道士常冠铁冠,于潜妇女皆插大银栉,长尺许,谓之蓬沓)。

这首诗,初看是苏东坡为刁铸建的野翁亭而写,实际上蕴含着对刁铸政绩的好评。“野翁来往溪山间”“翁言此间亦有乐”,乐在哪里?“非丝非竹非蛾眉”,乐在安民。何以见得?苏东坡自答:“我来观政问风谣,皆云吠犬足生牦。”也就是说,苏东坡去民间走走,听到了老百姓对县令刁铸的好评,他用一个典故来形容。《后汉书》记载,岑熙做魏郡太守时政清民安,连老百姓家看门狗也无所事事,脚底都长出了长毛。最后两句“但恐此翁一旦舍此去,长使山人索寞溪女啼”的意思说,如果县令刁铸离任,道士们会感到很落寞,民妇会为此流泪。

第二首诗告诉我们苏东坡了解了于潜的风土人情。苏东坡的《于潜女》一方面显示出他观察民风很仔细,另一方面显示出他遣词很传神:

青裙缟袂于潜女,两足如霜不穿屦。

觰沙鬓发丝穿杼,蓬沓障前走风雨。老濞宫妆传父祖,至今遗民悲故主。苕溪杨柳初飞絮,照溪画眉渡溪去。逢郎樵归相媚妩,不信姬姜有齐鲁。

在苏东坡笔下,我们仿佛看到,微风细雨中,江南女子在苕溪边柳树下轻盈地走来,青裙白衣飘飘。苏东坡问,这些女子的神态服饰,难道不是从吴越王时期一代代传下来的?于潜女子,她们夫妇相爱,安享渔樵之乐,看到这样的人和这样的美好生活,即使周文王治下的美女们也不能与于潜女子相比。

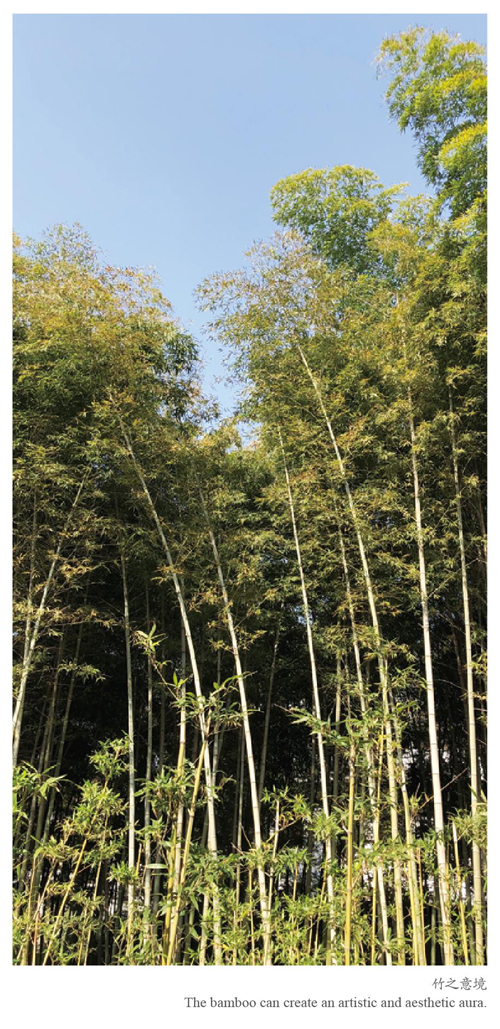

第三首诗告诉我们苏东坡游览了于潜的名胜古迹。正是由于这一次游览,苏东坡给我们留下了“宁可食无肉,不可使居无竹”的名句。

于潜县南旧有寂照寺,于潜僧慧觉在寂照寺出家。苏东坡一向喜欢结交佛家之人,到于潜顺便去了寂照寺,慧觉相陪游寺。寂照寺内有个绿筠轩,以竹点缀环境,十分幽雅,苏东坡看了很喜欢,就写下了这首《于潜僧绿筠轩》:

宁可食无肉,不可使居无竹。无肉令人瘦,无竹令人俗。人瘦尚可肥,士俗不可医。旁人笑此言,似高还似痴。若对此君仍大嚼,世间那有扬州鹤?

此君,用的是晋王徽之的典故。王徽之酷爱竹子,有一次他借住在一位朋友家里,见四周没有竹子,当即吩咐找人来种竹,他说:“何可一日无此君。”此君指的就是竹子。大嚼,也有典故,曹丕《与吴质书》有语:“过屠门而大嚼,虽不得肉,贵且快意。”扬州鹤,用的是《殷芸小说》故事,一群人相聚各谈志向,有说想当扬州刺史,有说想发财,有说想骑鹤上天做神仙。还有一人说,要“腰缠十万贯,骑鹤上扬州”,升官、发财、成仙都想得到。

这首诗的大意为:宁可没有肉吃,也不能让居住的地方没有竹子。没有肉吃会让人瘦削,如果看不到竹子就会让人变得很俗气。人如果瘦了还可变肥,人如果俗了就难以变清。旁人若果对此不理解,那幺请想一想:既要欣赏高雅的竹子,又要大块吃肉,这世上哪里会有“腰缠十万贯,骑鹤上扬州”,升官、发财、成仙都得到的好事呢?

Su Dongpo’s Inspection Tours When in Hangzhou

By Sima Yimin

When Wang Anshi (1021-1086), the prominent Northern Song (960-1127) statesman, pushed through his New Policies — a series of reforms he initiated as the chancellor under Emperor Shenzong (1048-1085), he courted much controversy as well as opposition. Among the many who voiced their objections were Su Shi (1037-1101), aka Su Dongpo, and his brother Su Zhe (1039-1112), for which they were both punished. The latter was banished to Chenzhou (present-day Huaiyang county in Henan province) in 1070, and a year later the former was sent to Hangzhou, demoted to serve as the controller-general (assistant prefect) in Hangzhou.

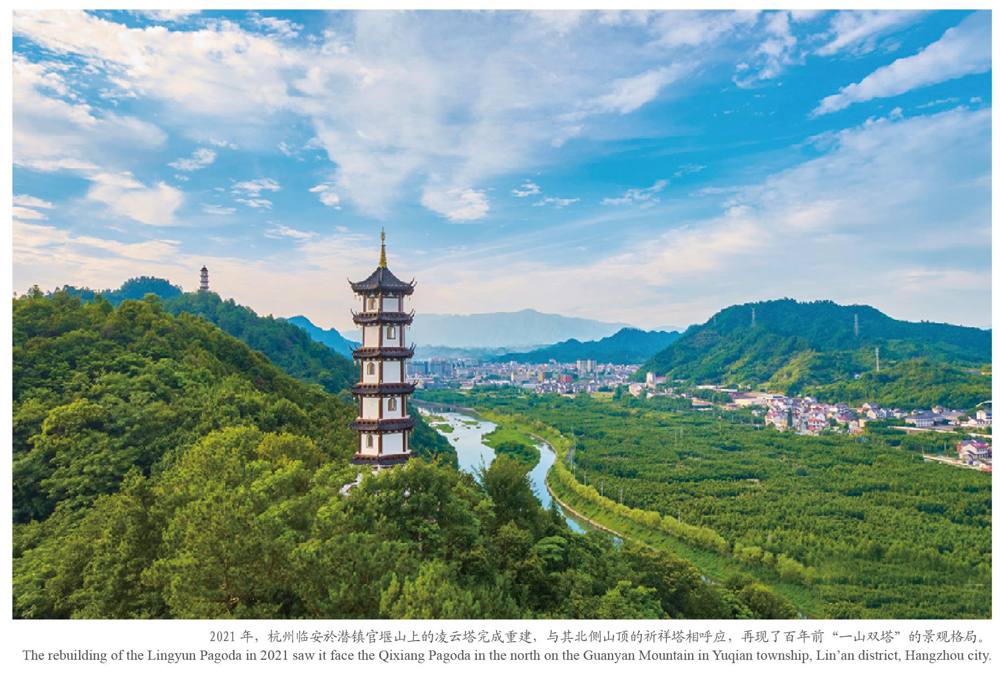

In the first lunar month of 1073, Su Dongpo was tasked with “shizheng” (literally “inspecting government”) in the counties of Fuyang, Xincheng and Yuqian. ?The so-called “shizheng” was a routine job for officials like Su, who would make regular inspection tours in local areas and review the local officials’ performance. No detailed records are available to show the details of Su’s inspection tour this time. Fortunately, Su kept the good habit of composing poems whenever and wherever he traveled. During this trip, he wrote quite a few, from which we may well glean information and piece together what transpired at the time.

Now, let’s take a look at the first poem of Su’s tour, entitled “To Fuyang and Xincheng, Judge Li Started Three Days in Advance, Waiting for Me at the Fengshui Cave”.

In spring mountains spring birds are chirping,

It wouldn’t do without my poetry-humming.

Along the river it’s a journey long,

It wouldn’t do without you.

At a golden crucian carp pond, you are not found,

For Dingshan village my chase is bound.

Passers-by say not far you are,

A young man riding a horse with grace.

The cave of wind and water long has a good name,

A mountain stream and nighttime block me from enjoy its fame.

The next morning, plum petals float on water under bridge I see,

It must be you tying the horse to the plum tree.

Three days you have been out of town,

Chiding you, your wife and children already ask when you’ll be around.

Kids of the day brag about running fast,

Is there anyone still like you just as patient?

Judging from the poem, Su Dongpo was in a very good mood, with his description of the sceneries along the way and his quips. However, it was the last couplet, ostensibly stating that kids of the day were fond of running as fast as they could and praising Judge Li for his thoroughness in the preparatory work (traveling out of town three days ahead), that became part of the evidence for his “crimes slandering the New Policies”.

In the Crow Terrace (nickname of the Imperial Office of the Censorate) Poetry Case in 1079, dozens of officials including Su Shi were charged with treason and offence against the emperor. Apparently, “kids of the day” (alternatively interpreted as “petty fellows”) was believed to be a barbed reference to those who were pushing for the reforms. Su admitted as much in his indictment: “… my line ‘Kids of the day brag about running fast,’ was a mockery of those who attempt to rush through all the new ideas.” Even far away from the imperial court, Su was still attached to the affairs of the capital. However, it should be noted that it was mostly a difference of opinions between Su and Wang Anshi than anything personal.

During his stay in Xincheng, Su came up with another two poems. In a modern rendering, the first poem roughly reads: The east wind knows I’m to the mountains, blowing and stopping days of raining. The clouds on the ridge seem to be wearing cotton hats, and the rising sun hanging on the treetops is like a bronze circular bell. The peach blossom by the low bamboo hedge nods and smiles at me, and the wicker by the sand stream dances to me. People living in the West Hills are very happy. They cook bamboo shoots for the hardworking spring plowmen. The second poem reads: The road of life is like the road I tread now, as I lead the horse to walk slowly by the stream. In the imperial court, even the men of talent fear the axe, and the tired war horses wish to hear the sound of gongs signaling retreat. Tea farmers are happy for the continuous drizzle, and in the depths of mountains many good friends of mine serve as upright officials. How many different ways are there in the world? Better ask the farmers in the field.

Then Su Dongpo went on to Fuyang and Xincheng before arriving in Yuqian, where he composed another three poems. In Yuqian, Su met Diao Zhu, the county magistrate of Yu Qian, and praised his performance. As he said in one of the poems, “I ask the common people in Yuqian, and they say house dogs have grown long hairs under the feet.” Su’s focus was not only on government affairs; he also took notice of local people and customs.

A countrywoman in farm dress and skirt blue

Reveals her frost-white bare feet for she wears no shoe.

A silver hairpin passing through her tousled hair,

Like shuttle in a loom she wades in wind and rain.

Hers is the dress that ancient palace maids did wear: People cannot forget their former master’s reign.

Willow catkins begin to fly beside the brook

Which sees her pass across with her penciled eyebrows.

The woodman comes back, they exchange an amorous look

And won’t believe on earth there is a happier spouse.

In the above poem, “A countrywoman of Yuqian”, translated into English by renowned Chinese translator Xu Yuanchong (1921-2021), Su depicted the happy life of locals through a countrywoman. It wouldn’t be fitting if Su hadn’t visited any places of interest or historic sites during his trips. In his stay in Yuqian, he went to Jizhao Temple — the name of the temple means “tranquility” (“Ji”) and “illumination” (“Zhao”), where he uttered the famous line “Live without meat I can, live without the bamboo I can’t.”

Known as one of the “Four Gentlemen”, the bamboo has long been held in high regard in Chinese art and literature. For Su Dongpo, no provision of meat will make one lose a few pounds, which one could still manage to grow back. However, no bamboo in sight will leave one in poor taste, which will hardly, if not impossible, be reversible.