东钱湖畔谒岳王

黄岚

辛丑年的一个冬日清晨,我再次前往东钱湖畔拜谒岳鄂王庙。远山隐约,舟楫静默,橘色的晨光将东钱湖染得一片温馨。偶尔有白鹭掠过静谧的湖面,早行的人们三三两两徜徉在湖畔,多幺美丽动人的画面。

岳鄂王庙,位于东钱湖西北岸的瓜屿上,因地形状似西瓜,俗称“西瓜庙”。当地老百姓又称之为岳王庙,称岳飞为岳老爷。时隔两年,风色如旧。庙前两根高高的旗杆,上有个方斗,四面各书一字,仔细一看,是“国泰民安”“风调雨顺”等字样,岳庙大门前的香炉上有点燃的香烛。问边上的嬷嬷,才知每逢初一,人们自发前来祭拜。转过身来,看到大门上“岳鄂王庙”四个金色大字,被廊前的两盏大红灯笼映得流光溢彩。旁边左右侧门上是“天地可表”“丹心万古”的门额,简约地概括了岳飞的品德与为人。大门前檐下抱柱上有一副对联:颠倒是非三字狱,激昂慷慨满江红。这上联说的是岳飞死于“莫须有”这三个字的冤狱,下联出自他那首千古名作《满江红》。大门边柱上的对联是:功建武宋千载后,绩树史册百世长。这是人们对岳飞一生功绩的公正评价。

现存岳鄂王庙是清代建筑,具有典型的宁波传统祀庙风格,为三进五开间建筑,由门楼、中殿、后殿及东西厢楼廊组成。我跨过门楼西边侧门,来到中殿。“还我河山”四个大字匾额下,一副楹联为浙江会稽道道尹黄庆澜所题:佐南宋中兴勋业方隆三字风波起冤狱,与东湖并寿英雄不死一泓秋水显忠魂。内有岳飞坐姿塑像,威武刚正,正气凛然。

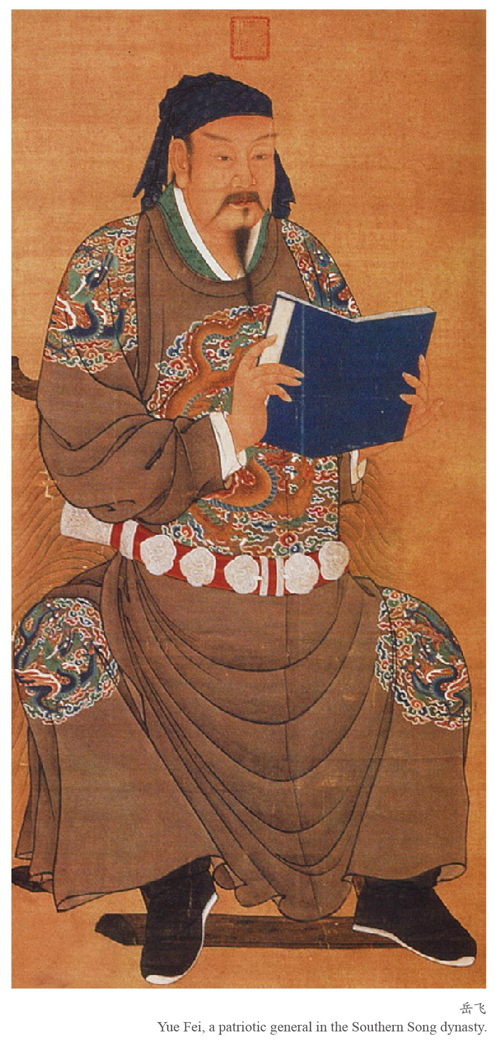

岳飞(1103—1142),字鹏举,相州汤阴(今河南省汤阴县)人。南宋时期抗金名将、军事家、战略家、民族英雄、书法家、诗人,位列南宋“中兴四将”之首。我小时就听过很多有关岳飞的故事,印象最深的是他一出生就遇到发大水,他坐在水缸中逃命的故事,以及岳母刺字这则故事。后来知道他非常自律,学习刻苦,练武勤奋,善于行军打仗。靖康之难发生在公元1127年,时金军南下,攻取北宋首都开封,掳走徽、钦二帝,导致北宋灭亡。岳飞等将领力挽狂澜,在攻打敌人、保家卫国过程中威名大振。他治军严明,奉行“仁义、智慧、信心、勇气、严格”的策略,使岳家军在行军中养成“冻死不拆屋,饿死不打掳”的优良作风。他曾计破金军的铁塔兵与拐子马于河南郾城,这是农耕民族以步兵完胜游牧民族骑兵的典型战例。然而,就在他带领北伐军收复中原失地、即将直捣金国首都时,却被宋高宗赵构以十二道金牌唤回。他知道这一回去,昔日的凌云壮志化为乌有,大宋美好江山难以完璧,于是仰面长叹,悲愤难当。中殿中间有一副楹联:三十功名尘与土,八千里路云和月。这两句诗直接拿来作为楹联,在格律上是有瑕疵的,但从意思看,瑕不掩瑜。看到这里,我脑海中自然浮现了这《满江红》的诗句:怒发冲冠,凭栏处、潇潇雨歇。抬望眼,仰天长啸,壮怀激烈。三十功名尘与土,八千里路云和月。莫等闲,白了少年头,空悲切。

作为将领,不怕征战,不怕浴血疆场,但却怕赋闲在家,那才是对他最大的打击。而此时的岳飞,唯有仰天长啸,壮怀激烈。只是靖康劫难的耻辱还没洗刷,将士文臣的仇恨,怎可以熄灭?不要让我空等白了这少年头,给我一驾战车,我要踏破贺兰山阙,直捣黄龙擒胡虏,然后再从头收拾这旧山河,还我百姓一个清明世界。此时,他怎幺可能想到,后面还有一个风波亭等着见证他的无奈憋屈和愤懑。他被诬告“谋反、叛逆”,岳飞以身上的“精忠报国”来辩护,来坦陈他的满腔爱国热情,审讯者无言以对。他们没有证据,却还是 在1141年除夕(1142年1月27日)之夜,以“莫须有”的罪名将岳飞赐死在风波亭,与他一同被害的还有他的儿子岳云与部下张宪。这是多幺令人愤慨的谋杀啊!岳飞被害后,狱卒隗顺偷偷将他的遗体运出临安至九曲丛祠,葬之北山。又移至杭州埋下,并用他的玉环系之遗体腰间作凭证,在平反后移葬西湖栖霞岭,是为现在的岳王墓。

可能会有许多人与我初次来岳鄂王庙一样疑惑,岳飞出生在河南,安葬在杭州西湖,为什幺在东钱湖畔建有纪念岳飞的庙?我请教了宁波鄞州的文史学者戴松岳老师,他说这个跟南宋的丞相史浩有关。因史浩有平反岳飞冤案的首功,乡民们乃自发在此建庙。他还提到现在介绍中称岳鄂王庙又称“岳众行祠”,这个“众”字有误,可能“岳公行祠”比较合理。

史浩(1106—1194),字直翁,号真隐,明州鄞县东钱湖人,南宋政治家、词人。史家在南宋一朝,先后出过三位丞相,号称“一门三丞相,四世两封王,五尚书七十二进士”,是南宋有名的世家大族,其中,史浩是史氏家族中的第一位丞相。史浩在拜相之后,头一件事就是为岳飞平反,他对宋孝宗说岳飞被杀是存之已久的冤案。提议恢复他的名誉官爵,应该让他的子孙享受俸禄,与冤案牵连的人都应予以平反昭雪。绍兴三十二年(1162)六月,宋孝宗赵眘一继位就下诏:“追复岳飞元官,以礼改葬。”十月,又正式恢复岳飞少保、武胜定围军节度使、武昌郡开国公的官爵,恢复岳飞的儿子们官职,封岳飞的孙子为官等。此后,南宋朝廷又追赠岳飞谥号“武穆”,这就是岳武穆的由来。宋宁宗时,追封岳飞为鄂王。为什幺被封为鄂王,有说是因为岳飞平反后,是鄂州最先请求为岳飞建立祠庙。而鄂州(今武汉)是岳飞收复襄阳失地时岳家军的大本营所在地。

转身回头,看到门楼背面檐下,挂着个道光年间“忠悬日月”匾额,左右楹联为:怒发冲冠一词显见争生志,奸臣当道三字竟成千古冤。这个奸臣当指秦桧了。在庙前点香烛敬祀的嬷嬷见我询问平日这里是否有游人时,便迫切地告诉我说,岳飞死得多冤呀,曾有个高人对岳飞说过“年底不出,预防天哭;有人毒害,秦字缺两点”,让岳飞提防点。“年底不出”应证岳飞被害时除夕说得过去,但“秦字缺两点”暗指毒害他的是秦桧的“秦”字有点说不通。这个禅意故事,在民间广为流传。说的是岳飞奉诏回临安时,一个禅师要他出家不要回去面帝,并说:“岁底不足,谨防天哭;奉下两点,将人害毒。”奉下两点,即指秦字。这位嬷嬷是住在附近村的,她每天早上来给岳老爷上茶,逢人宣讲岳飞故事。而这些故事在口口相传中稍有缺失或改变也是可以理解的。她还说到,以前的岳王庙里,有个跪着拜岳老爷的秦桧像呢,可惜现在早没了。我想起我们江南的早餐油条,俗称“油炸鬼(桧)”,就是暗指将捏成秦桧夫妻形象的面粉,放到油锅中去炸,以解人们对他毒害岳飞的愤慨。从这些民间故事中也可以看出,老百姓对岳飞是多幺的崇敬,而对奸臣又是多幺的痛恨。

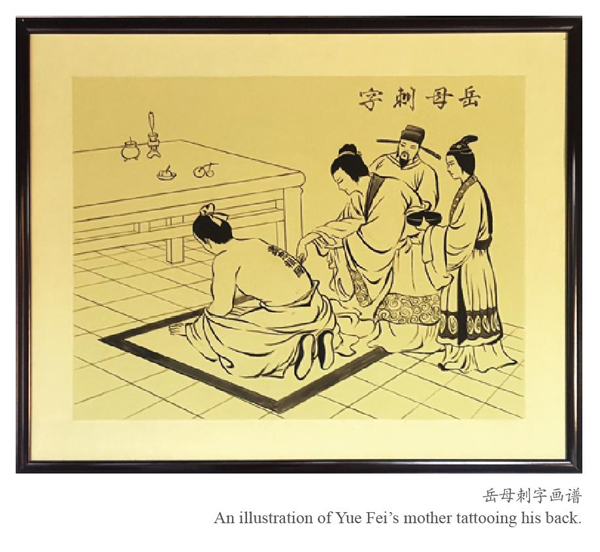

在祠庙的东西两侧廊下,有岳飞故事的画谱。最吸引人的便是岳母刺字这一幅。虽然小时早已熟知这个故事,但在看到壁画时,还是非常感动。金兵大举进攻时,岳飞投军报国,岳母在其背上刺上“精忠报国”四字,而国字少一点,表示国土有缺。那一针针,不只刺在岳飞的肌肤上,更刺在岳飞的心头上,成为他一生力量的源泉、行动的准则,以此来激励他忠诚爱国,誓死守卫国土。在我参观的时候,有一对父母带着七八岁的孩子也过来参观,父母在给孩子讲解这个故事。是的,这是绝好的爱国主义教育。我们的孩子应该了解我们的先贤故事,了解岳飞这位大英雄的故事。

记得我第一次来时正逢下雨,潇潇风雨飘落在东钱湖上,似乎看到了金宋对抗时的风雨。我当场写下一首七律《谒岳鄂王庙》:冬日钱湖浪寂寥,岳王庙外雨风飘。满江红寄河山志,三字狱伤宗稷祧。幸有后人平众怒,终留武穆飨今朝。长叹一代英雄泪,换见千年爱国潮。

是的,英雄的泪没有白流。只要看看那孩子专注的眼神就知道了。历史的河流滚滚向前,岳飞是我们民族的脊梁,他的爱国主义精神一直激励着我们。我们宁波人更深有感触。在抗击外敌时,岳飞的“还我河山”也成了一种象征,今天,我再次站在岳王庙,我知道千百年来,他精忠报国的精神早已深深植入我们的心灵。而我也为我们拥有这一座岳鄂王庙而感到庆幸,为能随时拜谒岳王而倍添荣耀,为能随时聆听岳王留给后人的教诲而深感荣幸。

Revisiting the King Yue’s Temple in Ningbo

By Huang Lan

I revisited the King Yue’s Temple (Yue E Wang Miao in Chinese, literary Yue King of E Temple, or King Yue’s Temple, dedicated to Yue Fei, King of E,) located along the Dongqian Lake in Ningbo on a winter morning in 2021. It is also known as the “watermelon temple” because it is on an islet that has the shape of a watermelon. Two flag poles stood tall in front of the temple, and a square dou (a Chinese bushel) is placed atop with some characters on each of its four sides, which read guotai minan (stable country and peaceful people), fengtiao yushun (good weather for the crops). The censers placed before the temple gate had lit candles in them, as visitors regularly pay their respect. The four-character Chinese name of the temple Yue E Wang Miao was written in golden above the gate, which beautifully glittered by the presence of two large-sized red lanterns in front of the corridor. On the side doors both at the left and the right there were some descriptions about Yue’s morality and personality, which were enhanced by the couplets on the surrounding pillars showing his life story and achievements.

The current King Yue’s Temple was first built in the Qing dynasty (1616-1911), a classic sacrifice temple of Ningbo traditions. It is a three-section five-room architecture, consisting of a gate tower, a middle hall, a rear hall with east- and west- wing corridors. Crossing the west door of the gate tower, I entered the middle hall, where a horizontal inscribed board reading huan wo he shan (give back our lost territories), a couplet and a sculpture of Yue Fei in sitting position could be found.

Yue Fei (1103-1142), courtesy name Pengju, was born in Xiangzhou (present-day Tangyin county, Anyang city) Henan province. He was a military general, militarist, calligrapher and poet during the Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279) and honored as “hero of the time”.

I heard many stories about Yue Fei when I was a child, and was really impressed by one of his managing to escape in a water tank and survived in a flood as a kid and another of his mother tattooing on his back. As I grew older, I also learned about his self-discipline, diligence in studying and practicing martial arts, and military talent.

During the Jingkang Incident, which took place in 1127 and led to the downfall of the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127), Yue fought bravely with his famously loyal and courageous “troops of the Yue family”, and was highly praised for his contribution. It was in this disastrous fight that Yue made his name. Later in another confrontation (1140), he beat a trap set by the strongest of Jurchen invaders strategically, a typical victory of infantry over cavalry. However, when he was trying to reclaim the lost territories and take the capital of Jin dynasty (1115-1234) with his warriors, he was recalled back by the emperor with 12 orders, which came in the form of 12 golden plagues. Knowing his ambitious old days would turn to dust, and his beloved homeland could no longer stay intact, Yue cried into the air with sad indignation, which was expressed in his best celebrated poem “Man Jiang Hong” (Entirely Red River).

As a general of ambition and patriotism, he could not bear watching the chances to fight for his homeland and protect his compatriots being robbed away. However, things went even worse unexpectedly. He was falsely accused of treason, no matter how justified and loyal he was and how hard he defended himself against it, and executed for a “could be true” crime at the Fengbo Pavilion. His son Yue Yun (1119-1142) was also put to death. After Yue Fei’s murder, a jailer stealthily escorted his body into Hangzhou to be buried there.

Some people may share my doubts about why there is a commemorate temple for Yue Fei in Ningbo, given that his birthplace is Henan, and his tomb is in Hangzhou. To clear that up, I asked Dai Songyue, a scholar on Ningbo’s cultural history, who explained that it had something to do with a prime minister of the Southern Song dynasty named Shi Hao (1106-1194), who hailed from Dongqian lake, Qin county (present-day Ningbo). As a newly appointed prime minister, he made it his priority for Yue’s mishandled case to be readdressed. Shi appealed to the emperor that Yue’s reputation and titular honors should be restored. So should those of his sons and grandsons, as well as other victims. Shi’s pleas were fully accepted and implemented accordingly. Later, the Song court gave Yue a posthumous title of King of E.

I turned around and saw a horizontal inscribed board with a couplet on the back of the gate tower. The characters on the board praised the great loyalty of Yue, while the ones on the couplet grieved over his tragic end and raged against Qin Hui (1090-1115), who conspired against Yue and eventually led to his death.

Yue is still loved and respected by local folks. There was this old woman to whom I talked at the entrance. She lived nearby and came here every morning to pay tribute to the hero by serving tea, and told his stories to everyone she came across.

These stories could be found drew on the walls of the east and west corridors inside the temple. Among all the folk tales, the one of Yue’s back tattoos was the most fascinating to me. Before Yue left home to join the army and defend his homeland against Jin’s invasion, his mother tattooed him on the back that read jing zhong bao guo (serve the country with the utmost loyalty) to remind Yue of his duty. These words were not only written on his back but deeply in his heart, becoming his lifetime source of courage and strength. During my visit, I saw a child of seven or eight was also there with the parents, who were explaining the stories to their kid.

And I was grateful to learn, by only looking at the child’s focused eyes, that the hero’s tears were not shed in vain. With the river of history rolling on, Yue Fei is always an inspiration of patriotism. Ningbo locals are feeling it profoundly. For example, during the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, Yue Fei’s appeal of “give back our lost territories” was also a spiritual pillar.

Today, as I stood at King Yue’s Temple again, I knew that his spirit of loyalty and service has been deeply implanted in the hearts and minds of Chinese people for thousands of years. I also feel fortunate enough to have this temple around, which we could visit at any time to be enlightened and educated with a humble heart.