夜宿水陆寺

司马一民

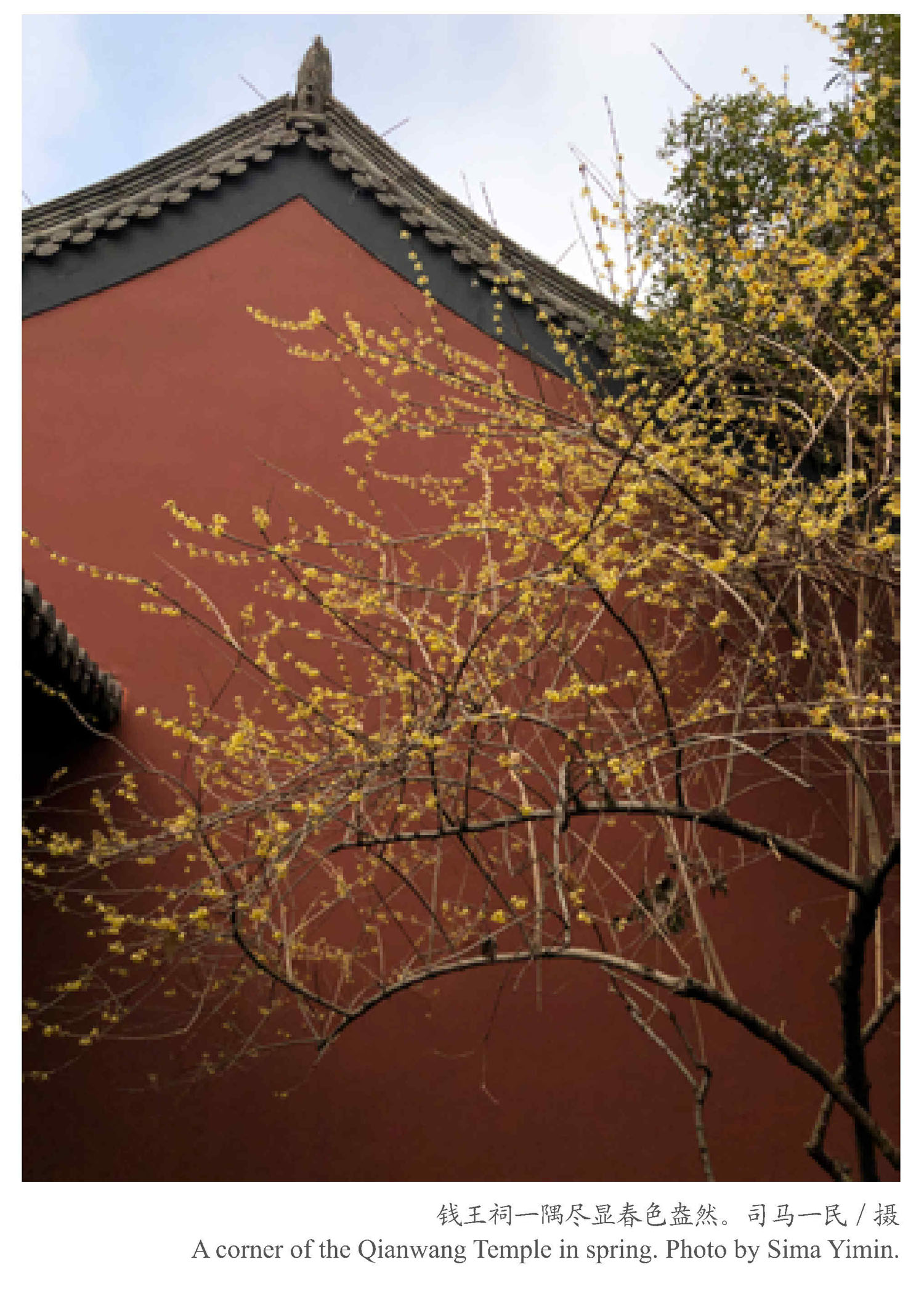

苏东坡两度在杭州为官,疏浚西湖、筑苏堤。读苏东坡写的许多与西湖相关的诗词,在后世人眼里,苏东坡在杭州的日子过得很潇洒。其实并不尽然,只不过这些吟咏西湖的诗词太过炫目,给人造成了错觉。不信,请读一读苏轼在杭州写的另外三首诗。苏东坡这三首诗都与一件事情有关——汤村开运盐河。

有必要先简单交代一下汤村。汤村在哪里?汤村就是现在的杭州市余杭乔司。南宋《乾道临安志》卷二载 :汤村镇“本仁和镇,端拱元年改,隶仁和县。”明永乐十一年(1413)镇为海潮所陷,后复涨为平陆。

清康熙《杭州府志》有载:乔司镇旧名汤村镇,在仁和东北五十九里,明永乐十一年(1413)曾为海潮所陷,清初设盐课司于此。民国《杭县志稿》载:“汤村镇市在南宋时即为两赤县(钱塘、仁和)十五镇市之一。”盐务历代都由朝廷专管,唐乾元二年(759),朝廷派盐铁使主管仁和盐业,乔司应是主管地域。乔司南面与钱塘江相近,杭州湾潮起潮落,沿江有盐场,清盐课司迁址于此,又改汤村为乔司,大约取盐课司乔迁之意。民国初年,乔司与临平、塘栖、三墩、瓶窑、良渚、留下并称七大镇。新中国成立后,1950年,杭县(1912年1月22日,并钱塘县、仁和县为杭县)在乔司镇南面区域设立盐区。1953年,因乔司镇翁中乡全部及翁东、翁西乡大部坍入钱塘江中,盐区撤销,盐业生产随之趋缓,直至停产。

回过头来再说苏东坡与汤村开运盐河的关系。

北宋时汤村(乔司)的食盐生产已具相当规模,外运靠牛车马车运输已不能满足,朝廷决定改为水运,从汤村(乔司)开凿一条河直达大运河,用来专门运送食盐。北宋熙宁五年(1072)十月,身为杭州通判的苏东坡承担了“督开”汤村运盐河的任务。其间,他写了三首诗纪事。两首诗是《是日宿水陆寺寄北山清顺僧二首》,还有一首诗是《汤村开运盐河雨中督役》。读这三首诗,可以看到繁华背后的辛酸。

苏东坡为什幺夜宿水陆寺?办事认真的苏东坡,为了“督役”运盐河工程,就近找了个地方过夜,免得杭州城里与汤村(乔司)来回跑费工夫,大约水陆寺是离汤村(乔司)比较近又适合夜宿的地方。

杭州现在仍然有一条巷叫水陆寺巷,巷名因寺名而起。水陆寺巷东起东清巷,西至新华路南段。宋代时名水陆寺巷、三营巷,明代称全三营巷,清代又复称水陆寺巷。这一带吴越国时设大路营,宋代有第三指挥所(营)在那里,所以叫三营巷、全三营巷。

历史上杭州有三个水陆寺:一在仁和城外,称外水陆寺;一近望江门,称上水陆寺;一在平安坊,称下水陆寺。估计苏东坡夜宿的水陆寺在仁和城外,即杭州北部。

我们现在来说说这三首诗。

先说《是日宿水陆寺寄北山清顺僧二首》:

其一

草没河堤雨暗村,寺藏修竹不知门。

拾薪煮药怜僧病,扫地烧香净客魂。

农事未休侵小雪,佛灯初上报黄昏。

年来渐识幽居味,思与高人对榻论。

其二

长嫌钟鼓聒湖山,此境萧条却自然。

乞食绕村真为饱,无言对客本非禅。

披榛觅路冲泥入,洗足关门听雨眠。

遥想后身穷贾岛,夜寒应耸作诗肩。

清顺,字颐然,杭州诗僧,苏东坡与他有诗词唱和,这两首诗就是寄给清顺的。前一首诗描写水陆寺幽寂的环境,寺僧的平淡生活,字里行间透着清冷。后一首诗描写了苏东坡“督役”生活的清苦,“乞食绕村真为饱”是生活上的清苦,“无言对客本非禅”是精神上的清苦。苏东坡与佛有缘,在各地都有僧友,喜欢谈禅,如今冷落在水陆寺里只为夜宿,夜深人静不由得思念在杭州的僧友,提笔写两首诗排遣一下郁闷的心情。

其实,苏东坡之所以心情郁闷,不仅仅是夜宿水陆寺的孤独,还因为开凿运盐河劳工的辛苦。

他写给弟弟苏辙的诗《汤村开运盐河雨中督役》,就吐露了这种悲悯的心声:

居官不任事,萧散羡长卿。胡不归去来,滞留愧渊明。盐事星火急,谁能恤农耕。薨薨晓鼓动,万指罗沟坑。天雨助官政,泫然淋衣缨。人如鸭与猪,投泥相溅惊。下马荒堤上,四顾但湖泓。线路不容足,又与牛羊争。归田虽贱辱,岂失泥中行。寄语故山友,慎毋厌藜羹。

这首诗是开凿运盐河劳工辛苦劳作的写实,“人如鸭与猪,投泥相溅惊”,只为了“盐事星火急”,“谁能恤农耕”?面对这样的场景,苏东坡肯定心情很沉重,但官不由身,他能咋样?心里的郁闷只能向亲人倾诉。

苏辙收到哥哥苏东坡的《汤村开运盐河雨中督役》,当即回了一首诗《和子瞻开汤村运盐河雨中督役》:

兴事常苦易,成事常苦难。不督雨中役,安知民力殚。年来上功勋,智者争雕钻。山河不自保,疏凿非一端。讥诃西门豹,仁智未得完。方以勇自许,未恤众口叹。天心闵劬劳,雨涕为泛澜。不知泥滓中,更益手足寒。谁谓邑中黔,鞭箠亦不宽。王事未可回,后土何由乾。

心意相通又手足情深的两兄弟,只能互相安慰:“不督雨中役,安知民力殚。”

Su Dongpo’s Overnight

Stay at the Shuilu Temple

By Sima Yimin

In his two terms of office in Hangzhou — first between 1071 and 1074 as the assistant prefect and then between 1089 and 1091 as the prefect, Su Dongpo (aka Su Shi, 1037-1101) oversaw the dredging the West Lake, built the Su Causeway, and finished a host of projects that had improved the livelihood of local people. Of course, he also composed some of the most memorable poems in the history of Chinese poetry. When one reads Su’s verses on the West Lake now, perhaps one cannot help but think his life in Hangzhou was all gaiety and joy. But that perhaps is a gross misunderstanding, thanks to all the dazzling lines about the West Lake. Here are several poems by Su Shi that show another side of his life in Hangzhou.

The poems were all about one subject, the digging of a salt transportation canal in Tangcun. Before proceeding to the poetry, it is necessary to give a brief account of Tangcun.

Tangcun is in fact present-day Qiaosi in Hangzhou’s Yuhang district. Historical records from the Song dynasty (960-1279) to the Qing dynasty (1616-1911) have documented Tangcun. For example, according to Hangzhou Fuzhi, or the Gazetteer of Hangzhou Prefecture, published in 1686, “Qiansi township, formerly named Tangcun township, is located 59 li to the northeast of Renhe county [part of present-day Hangzhou city proper] and was once inundated by tides in 1413. In the early days of the Qing, a salt tax office was set up here.”

The establishment of such an office had a lot to do with the location of Tangcun (or Qiaosi). Close to the Qiantang River and the tides of the Hangzhou Bay, the place was ideal for the production of salt. In the Northern Song period (960-1127), salt was produced on quite a big scale in Tangcun, and transporting salt through oxen carts and horse wagons could no longer meet the demand. Therefore, the imperial court decided to transfer salt by water instead; a canal was thus built from Tangcun to the Grand Canal which was specifically used to for salt transport.

Coincidentally, Su was the one tasked to supervise its construction. In October 1072, he started out on his duties and it was during that period that he penned the aforementioned poems.

In “Two Poems Written While Staying the Night at the Shuilu Temple, and Sending Them to Monk Qingshun on the North Hill”, Su described the tranquility of the temple (“hidden in bamboo groves I can’t find its gate”), his longing for a hermitlike life (“as I grow old, reclusive life I increasingly desire) in the first and the challenging conditions he faced executing his duties (“I beg around the village for food, just to fill up my belly”, “chopping down overgrown bushes, I seek path in muddy waters”) in the second.

Ever a conscientious official, Su stayed at the temple that night only because it was close to the canal they were constructing, which saved the hassle of traveling back and forth from the city center. And Qingshun the monk was one of the many Buddhist poets that Su had befriended.

But it was the hardship that the laborers digging the canal had to go through that truly upset Su and made him lament “who cares about these peasants and their livelihood?”, in another poem he wrote to his younger brother Su Zhe (1039-1112), titled “Supervising the Construction of the Salt Canal in Rain at Tangcun”. A line of the verse reads, “they [the laborers] are like ducks and pigs, startled by the splash of mud water they dive in”; all these were just because “the salt business is a most urgent matter”. While commiserating with these laborers, Su could do little but follow the orders of the imperial court.

Perhaps a line in Su Zhe’s reply poem is able to best capture their mood, “not supervising the project in rain, you’d never know people in pain”.

scicat.cn202203282234