隗闯 张萌 武瑞 王玉亭 王钥 周宇

[摘要] 目的 探讨细胞集落刺激因子1受体(CSF1R)抑制剂PLX5622对C57BL/6小鼠空间型学习与记忆的影响。方法 16只健康雄性C57BL/6小鼠随机分为实验组和对照组,各8只。实验组小鼠连续2周投食含PLX5622的鼠粮,对照组小鼠投食等量的标准鼠粮。采用Morris水迷宫实验检测两组小鼠的空间型学习力与记忆力;应用荧光免疫组化法测定两组小鼠海马区域小胶质细胞的密度。结果 水迷宫结果显示,与对照组相比,实验组小鼠在圆台所在象限探索的时长百分比明显下降(t=3.556,P<0.01),逃避潜伏期、穿越圆台次数、游泳速度差异无显著性(P>0.05)。荧光免疫组化结果显示,与对照组相比,实验组小鼠每平方毫米海马区域小胶质细胞的数量明显减少(t=11.430,P<0.01),成熟神经元数量两组比较差异无显著性(P>0.05)。结论 海马区域小胶质细胞清除不影响小鼠空间学习与记忆获取,但削弱小鼠的空间型记忆力。

[关键词] 小神经胶质细胞;迷宫学习;海马;小鼠

[中图分类号] R338.2 ?[文献标志码] A ?[文章编号] 2096-5532(2020)02-0173-04

doi:10.11712/jms.2096-5532.2020.56.089 [开放科学(资源服务)标识码(OSID)]

[网络出版] http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/37.1517.R.20200519.1430.004.html;2020-05-20 08:57

[ABSTRACT] Objective To investigate the effect of the colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor inhibitor PLX5622 on the spatial learning and memory in C57BL/6 mice. ?Methods A total of 16 healthy male C57BL/6 mice were randomly divided into control group and experimental group, with 8 mice in each group. The mice in the experimental group were given PLX5622-based chow diet for 2 consecutive weeks, and those in the control group were given an equivalent amount of normal chow diet. Morris water maze test was conducted to evaluate the spatial learning and memory of the mice. Fluorescent immunohistochemistry was used to determine the density of microglial cells in the hippocampus of the mice. ?Results Morris water maze test showed that the searching time (%) for the platform in the target quadrant was significantly reduced in the experimental group compared with that in the control group (t=3.556,P<0.01), while the escape latency, number of platform crossings, and swimming speed were not significantly different between the two groups (P>0.05). Fluorescent immunohistochemistry showed that the number of microglial cells per square millimeter of the hippocampus was significantly reduced in the experimental group compared with that in the control group (t=11.430,P<0.01), while the number of mature neurons was not significantly different between the two groups (P>0.05). ?Conclusion Microglial cell elimination in the hippocampus has no significant effect on spatial learning and memory acquisition in mice, but it reduces the spatial memory of the mice.

[KEY WORDS] microglia; maze learning; hippocampus; mice

越来越多的实验结果显示,神经炎症和多种神经退变性疾病(如阿尔兹海默症和帕金森病等)的發生相关度很大[1-4]。小胶质细胞是神经并发炎症的一个重要的参与者[5-6]。在健康的情况下,小胶质细胞可以维持大脑的微环境平衡,保护其神经元;中枢神经系统受到损伤或感染时,小胶质细胞发生炎症反应性激活即M1极化,高表达炎性细胞因子,同时细胞形态发生改变,吞噬细胞碎片,利于损伤修复;而过度激活的小胶质细胞则引起促炎性细胞因子大量增加,诱导慢性炎症并导致神经元死亡[7-12]。集落刺激因子1受体(CSF1R)抑制剂PLX5622,可以阻断血小板衍生的生长因子家族配体CSF1与单核类细胞和外周巨噬细胞型细胞特异的酪氨酸激酶型受体CSF1R的结合,从而清除脑内的小胶质细胞。PLX5622不影响小鼠日常活动,在停用该药物1周后,脑内的小胶质细胞基本恢复正常水准[12-15]。为了探究小胶质细胞的消除是否影响小鼠的学习与记忆,本研究采取PLX5622喂食清除小鼠脑内小胶质细胞[16],观察小胶质细胞的清除对正常的野生型小鼠空间型学习与记忆的影响。

1 材料与方法

1.1 实验动物及分组

SPF级12周龄的雄性C57BL/6小鼠16只,体质量(30±2)g,由北京维通-利华实验动物有限公司供应。小鼠于20 ℃、日夜循环光照状态下喂养,可随意进食、饮水、活动。随机将小鼠分为对照鼠粮喂食组(对照组)、PLX5622鼠粮喂食组(实验组),各8只。PLX5622鼠粮(每千克含PLX5622量为1 200 mg)和对照鼠粮(不含PLX5622,其余成分与实验组一致)购自Plexxikon公司。

1.2 给药方法

实验开始前14 d启动 PLX5622 喂食或对照喂食,并在实验期间维持。喂食期间小鼠单笼饲养并每天抚慰2 min以降低其焦虑水平[15]。小鼠每天定点定量喂食(每只4 g/d),同时记录食用量。

1.3 Morris水迷宫实验

Morris 水迷宫包括装有水的圆柱状水箱、隐匿在水平面下的圆台以及一系列视频主动拍摄和处理数据系统,可以用来评价小鼠的空间型学习与记忆能力。每只小鼠每天进行4次空间定位游泳训练,记下小鼠每天寻找水下圆台的逃避潜伏期,评价小鼠的空间型学习能力[17]。连续训练6 d后进行为期60 s的空间型记忆测试,记录小鼠穿过圆台次数、象限探索时长的百分比、游泳速度等,以评价小鼠的空间型记忆[18]。

1.4 荧光免疫组化检测

水迷宫实验完成后,两组小鼠以40 g/L多聚合甲醛经心灌注后取脑,固定4 h,放入含有300 g/L蔗糖的混合液中沉糖。用包埋剂OCT包住脑组织,快速冷冻、切片,切片厚度40 μm。将切片移到0.01 mol/L PBS混合液中保存。行常规荧光免疫组化检测:脑切片以0.01 mol/L PBS混合液洗净后,加抗体封闭液在常温摇床上封闭1 h,然后加一抗4 ℃摇床上孵育72 h;以0.01 mol/L PBS混合液清洗3次后,加荧光二抗在常温摇床上孵育1~2 h(暗光下);再以0.01 mol/L PBS混合液洗清干净后,将切片转移到载玻片上铺片、晾干,封片剂封片。应用Leica DMi8倒置荧光显微镜和10倍干物镜捕获荧光图像,Image J图像阈值测量工具对择定海马脑域(ROI)小胶质细胞染色密度进行量化分析。所用一抗NeuN抗体(1∶1 000)和Iba1抗体(1∶500)均购于美国Cell Signaling Technology 公司,荧光二抗Alexa-568 goat anti-mouse IgG(1∶2 000)和Alexa-488 goat anti-rabbit IgG(1∶2 000)购自美国Invitrogen公司。

1.5 统计学处理

应用Graph Pad Prism 6软件进行统计学分析,计量资料结果以±s表示,两组比较采取成组t检验;多组数据比较采用双因素方差分析,然后采用Tukeys多重對比法进行两两对比。以P<0.05表示差异有统计学意义。

2 结 ?果

2.1 两组小鼠空间型学习能力比较

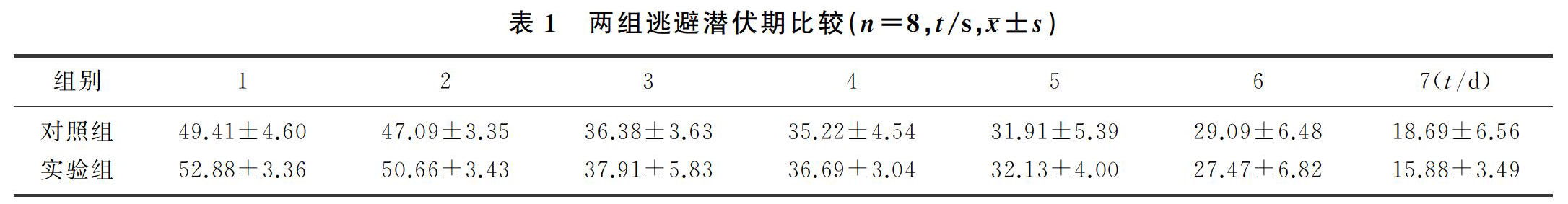

双因素方差分析显示,训练天数和药物处理两种因素对小鼠的逃避潜伏期不存在交互作用(F=0.127,P>0.05)。药物处理对小鼠逃避潜伏期不存在作用,两组各时间逃避潜伏期比较差异无显著性(P>0.05)。训练天数对小鼠空间型学习能力有影响(F=11.940,P<0.01),两组小鼠第7天逃避潜伏期均较第1天缩短,差异有显著性(P<0.01)。表明小鼠的空间型学习不受PLX5622投食的影响。见表1。

2.2 两组小鼠空间型记忆能力对比

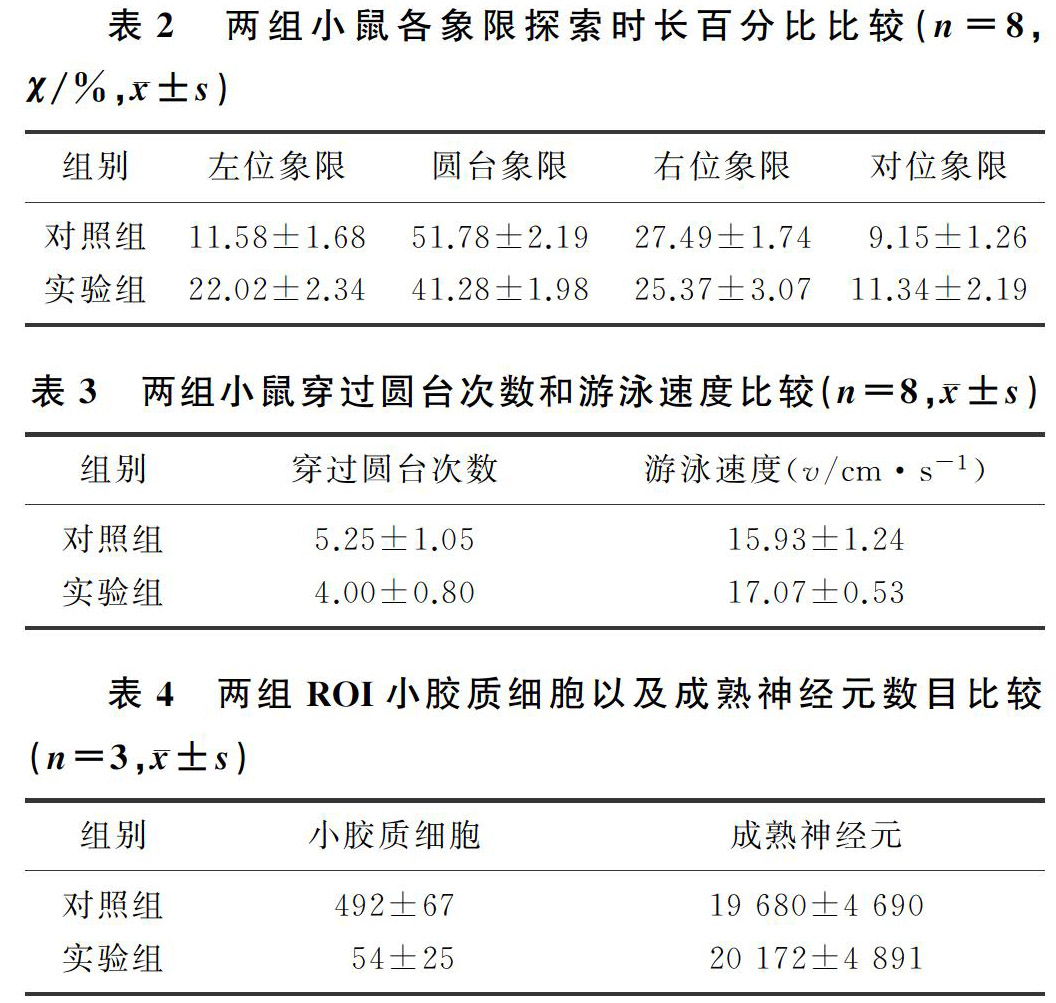

双因素方差分析显示,药物处理和迷宫象限两种因素对小鼠的探索时长百分比有交互作用(F=8.473,P<0.01)。药物处理对小鼠探索时长百分比不存在作用,两组各象限探索时长百分比差异无显著性(P>0.05)。迷宫象限对小鼠探索时长百分比有影响(F=111.400,P<0.01),实验组和对照组小鼠在圆台象限的探索时长百分比均显著高于其他3个象限,差异有统计学意义(P<0.01),说明经过6 d练习两组小鼠均获得了空间型记忆。两组圆台象限探索时长百分比比较,差异有显著性(t=3.556,P<0.01);两组穿越圆台的次数及游泳速度比较,差异无显著性(P>0.05)。见表2、3。

2.3 两组小鼠ROI小胶质细胞比较

小鼠ROI小胶质细胞Iba1免疫染色阳性(绿色荧光),成熟神经元呈NeuN免疫染色阳性(红色荧光)。荧光定量分析结果显示,实验组小鼠ROI每平方毫米小胶质细胞的数目明显少于对照组(t=11.430,P<0.01);而两组小鼠ROI成熟神经元数量差异无显著性(P>0.05)。见表4。

3 讨 ?论

小胶质细胞不仅是大脑的免疫型细胞,同时在大脑的发育、神经元的网络结构和功能稳态,以及中枢类神经受损与修复等生理过程中都起着重要的调节作用[19]。小胶质细胞是脑中存在的巨噬细胞,但是由于其独特的表型和中枢神经系统中微环境的严格调节,小胶质细胞主要负责消除可能危害中枢神经系统的微生物、坏死细胞、多余的突触、蛋白质的聚集体以及其他颗粒和可溶性的抗原等[20-21]。小胶质细胞是脑内促进炎性细胞因子产生的主要来源,是中枢性神经炎症的关键递质,可以诱导或调节广泛的细胞炎症反应。小胶质细胞的功能变化与老化以及神经变性相关度很高[5,22-23]。

有研究显示,小胶质细胞的存活离不开CSF1R信号;而PLX5622是最新研制成功的特异度很高的CSF1R抑制剂,其特点是可口服,可透过血-脑脊液屏障,对小胶质细胞的清除率高,连续给小鼠喂食2周PLX5622可以清除脑中90%以上的小胶质细胞[24]。同时,PLX5622还具有不影响小鼠基本生理活动和行为的特点[11,25]。

本研究通过投食PLX5622消除脑内小胶质细胞,采取Morris水迷宫实验评估小胶质细胞消除对小鼠空间型学习与记忆的影响,结果显示,与对照组比较,实验组小鼠脑内小胶质细胞数量显著减少,与相关研究结果相一致[12,15]。本文研究结果显示,海马内小胶质细胞清除对小鼠的空间型记忆力有一定的抑制作用,表现为实验组在圆台所在象限的探索时长的百分比显著低于对照组,说明生理状况下海马内小胶质细胞参与空间型记忆的调节。本文结果还显示,两组小鼠定位航行的圆台逃避的潜伏期和运动速度差异无显著性,两组小鼠空间探索时在圆台所在象限逗留的时长均较其他象限明显延长,表明PLX5622诱导的小胶质细胞清除并不影响小鼠的空间探索、运动协调、空间型学习与记忆获取。本文结果可為后续开展小胶质细胞对阿尔茨海默症等神经退变性疾病的影响及机制研究奠定基础。

综上所述,生理状态下海马区小胶质细胞对小鼠的空间型记忆有重要的调节作用。其分子和细胞机制需要深入的研究。衰老、神经变性和慢性应激都可能导致认知与情感障碍,同时伴随着小胶质细胞的异常激活和促炎性改变。小胶质细胞异常激活导致记忆受损已有不少报道[20,26-31]。因此,清除异常激活的小胶质细胞可能为认知障碍的治疗或干预提供新的思路和靶点。

[参考文献]

[1] LIU Y, CHU J M T, YAN T, et al. Short-term resistanceexercise inhibits neuroinflammation and attenuates neuropathological changes in 3xTg Alzheimers disease mice[J]. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 2020,17(1):4.

[2] GITLER A D, DHILLON P, SHORTER J. Neurodegenerative disease:models,mechanisms,and a new hope[J]. Disease Models & Mechanisms, 2017,10(5):499-502.

[3] MUSELLA A, FRESEGNA D, RIZZO F R, et al. Prototypi-cal proinflammatory cytokine (IL-1) in multiple sclerosis: role in pathogenesis and therapeutic targeting[J]. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets, 2020,24(1):37-46.

[4] HUANG L K, CHAO S P, HU C J. Clinical trials of new drugs for Alzheimer disease[J]. Journal of Biomedical Science, 2020,27(1):18-30.

[5] SROOR H M, HASSAN A M, ZENZ G, et al. Experimental colitis reduces microglial cell activation in the mouse brain without affecting microglial cell numbers[J]. Scientific Reports, 2019,9(1):20217-20228.

[6] HOCQUEMILLER M, HEMSLEY K M, DOUGLASS M L, ? et al. AAVrh10 vector corrects disease pathology in MPS ⅢA mice and achieves widespread distribution of SGSH in large animal brains[J]. Molecular Therapy Methods &Clinical Deve-lopment, 2020,17:174-187.

[7] HANSEN D V, HANSON J E, SHENG M. Microglia in Alzheimers disease[J]. The Journal of Cell Biology, 2018,217(2):459-472.

[8] COLONNA M, BUTOVSKY O. Microglia function in the central nervous system during health and neurodegeneration[J]. Annual Review of Immunology, 2017,35:441-468.

[9] SHINOHARA M, TASHIRO Y, SHINOHARA M, et al. Increased levels of Aβ42 decrease the lifespan of ob/ob mice with dysregulation of microglia and astrocytes[J]. FASEB Journal, 2019,34(2):2425-2435

[10] PIERS T M, COSKER K, MALLACH A, et al. A locked immunometabolic switch underlies TREM2 R47H loss of function in human iPSC-derived microglia[J]. FASEB J, 2019,34(2):2436-2450.

[11] ROSIN J M, VORA S R, KURRASCH D M. Depletion of embryonic microglia using the CSF1R inhibitor PLX5622 has adverse sex-specific effects on mice, including accelerated weight gain, hyperactivity and anxiolytic-like behaviour[J]. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2018,73:682-697.

[12] SPANGENBERG E, SEVERSON P L, HOHSFIELD L A, et al. Sustained microglial depletion with CSF1R inhibitor impairs parenchymal plaque development in an Alzheimers disease model[J]. Nature Communications, 2019,10(1):3758-3778.

[13] HATTON C F, DUNCAN C J A. Microglia are essential to protective antiviral immunity: lessons from mouse models of viral encephalitis[J]. Frontiers in Immunology, 2019,10(1):2656-2664.

[14] HUPP S, ILIEV A I. CSF-1 receptor inhibition as a highly effective tool for depletion of microglia in mixed glial cultures[J]. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 2019,332(1):108537.

[15] ALLEN B D, APODACA L A, SYAGE A R, et al. Attenuation of neuroinflammation reverses Adriamycin-induced cognitive impairments[J]. Acta Neuropathologica Communications, 2019,7(1):186-200.

[16] TODD L, PALAZZO I, SUAREZ L, et al. Reactive microglia and IL1β/IL-1R1-signaling mediate neuroprotection in excitotoxin-damaged mouse retina[J]. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 2019,16(1):118-136.

[17] ZHOU Cui, LI Mengyu, LIU Zhaoxia, et al. Effects of moxibustion on the structure and function of blood brain barrier in Alzheimers disease model rats[J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Physiology, 2019,35(5):443-446.

[18] MO Jun, CHEN Tingkai, YANG Hongyu, et al. Design, synthesis, in vitro and in vivo evaluation of benzylpiperidine-linked 1,3-dimethylbenzimidazolinones as cholinesterase inhi-bitors against Alzheimers disease[J]. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry, 2020,35(1):330-343.

[19] AROUT C A, WATERS A J, MACLEAN R R, et al. Minocycline does not affect experimental pain or addiction-related outcomes in opioid maintained patients[J]. Psychopharmacology, 2019,236(10):2857-2866.

[20] BURETA C, SETOGUCHI T, SAITOH Y, et al. TGF-beta promotes the proliferation of microglia in vitro[J]. Brain Sciences, 2019,10(1):20-28.

[21] YAVARPOUR-BALI H, GHASEMI-KASMAN M, SHOJAEI A. Direct reprogramming of terminally differentiated cells into neurons: a novel and promising strategy for Alzheimers disease treatment[J]. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 2020,98(1):109820-109831.

[22] 余軍,赵维星,杜春彦,等. 胆碱改善脂多糖诱导的小鼠中枢神经系统炎症反应及认知功能障碍[J]. 南方医科大学学报, 2017,37(5):600-606.

[23] YIRMIYA R, RIMMERMAN N, RESHEF R. Depression as a microglial disease[J]. Trends in Neurosciences, 2015,38(10):637-658.

[24] JOVANOVIC J, LIU X, KOKONA D, et al. Inhibition of inflammatory cells delays retinal degeneration in experimental retinal vein occlusion in mice[J]. Glia, 2020,68(3):574-588.

[25] CARROLL J A, CHESEBRO B. Neuroinflammation, microglia, and cell-association during prion disease[J]. Viruses, 2019,11(1):65-84

[26] OMERAGIC A, SAIKALI M F, CURRIER S, et al. Selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma modulator, INT131 exhibits anti-inflammatory effects in an EcoHIV mouse model[J]. FASEB Journal, 2019,34(2):1996-2010.

[27] ESTRADA S M, THAGARD A S, DEHART M J, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor Nr4a1 mediates perinatal neuroinflammation in a murine model of preterm labor[J]. Cell Death & Disease, 2020,11(1):11-25.

[28] LIU Y, GIVEN K S, DICKSON E L, et al. Concentration-dependent effects of CSF1R inhibitors on oligodendrocyte progenitor cells ex vivo and in vivo[J]. Experimental Neurology, 2019,318:32-41.

[29] KONDO Y, MATSUSHIMA A, NAGASAKI S, et al. Factors predictive of the presence of a CSF1R mutation in patients with leukoencephalopathy[J]. European Journal of Neurology, 2020,27(2):369-375.

[30] ANDERSON S R, ROBERTS J M, ZHANG J, et al. Deve-lopmental apoptosis promotes a disease-related gene signature and independence from CSF1R signaling in retinal microglia[J]. Cell Reports, 2019,27(7):2002-2013.

[31] DAIDA K, NISHIOKA K, LI Y, et al. CSF1R mutation p.G589R and the distribution pattern of brain calcification[J]. Internal Medicine (Tokyo, Japan), 2017,56(18):2507-2512.

(本文編辑 黄建乡)

- 初中物理实验教学中核心素养的培养策略

- 浅谈信息技术与高中数学教学的融合应用研究

- 立足化学实验凸显多彩世界

- 探讨核心素养下的初中物理教学策略

- 高中数学教学中数形结合思想的整合研究

- 基于高考的高中数学思想教学研究

- 如何引导学生掌握高中物理解题方法

- 二次函数在平面几何的应用研究

- 高中化学学习方法与策略

- 举一反三的能力源自于夯实的基础

- 数形来结合,巧把问题解

- 高中数学三角函数教学策略探究

- 构建物理模型解决物理问题

- 初中物理教学中存在的问题及原因分析

- 高中物理习题教学中引导学生学会分析习题

- 初中物理创新实验题的类型及解法分析

- 高中化学解题中的逆向思维探析

- 初探演示法在初中数学课堂的创新和应用

- 高中物理反思式教学的实践与研究

- 初中物理基于兴趣的分享式科学探究的实践研究

- 高中物理项目式教学的实施策略

- 让初中学生数学思维走向灵动

- 如何教会学生读题

- 中学化学教学中学生问题意识的培养

- 浅谈将学科核心素养与教学评一致性进行统一的教学实践

- pass's

- pass sb by

- pass sb off as sb/sth / pass yourself off as sb/sth

- pass sb/sth off (as sb/sth)

- pass sb/sth off as sth

- pass sth along (to sb)

- pass sth down

- pass sth off as sth

- pass sth on

- pass sth on (to sb)

- pass sth out

- pass sth through (to sb)

- pass sth up

- pass sth ↔ around

- pass sth ↔ down

- pass sth ↔ on

- pass the buck

- pass-the-hat

- pass the time

- pass the time of day

- passthrough

- pass-through

- pass-up

- pass up

- pass-up-on

- 瞎起哄

- 瞎跑

- 瞎路

- 瞎跳

- 瞎蹦

- 瞎转

- 瞎转圈

- 瞎转圈子

- 瞎转悠

- 瞎转转

- 瞎道儿

- 瞎铺排

- 瞎闯

- 瞎闯过不了五关

- 瞎闹

- 瞎马临池

- 瞎马深池

- 瞎马自惊

- 瞎驴上不去板桥

- 瞎驴子拉磨——转回原处

- 瞎驴对破磨——将就

- 瞎驴推磨盘

- 瞎驴牵了槽上——喂你不知喂你

- 瞎驴牵了槽上——喂(为)你不知喂(为)你

- 瞎驴转磨——总是按自己的辙走