【Abstract】English borrows a lot of words from other languages. Chinese and Japanese loanwords in English have a deep cultural and historical background. This paper makes a comparative analysis of Chinese and Japanese loanwords in English based on the OED, concluding their amounts, naturalization process,the characteristics of word formation and so forth.

【Key words】Chinese loanwords; Japaneseloanwords; ?Comparison; the OED

【作者簡介】王梓寒,北京大学外国语学院。

Ⅰ. Introduction

It is a common phenomenon that languages borrow words from each other. With the development of society and economy and the increasing frequency of cultural exchanges, this kind of borrowing becomes increasingly common. English is considered to be the most hybridized tongue, and borrowing has recently become the major way of making new English words. It is estimated that English borrowings constitute up to 80 percent of the modern English vocabulary. From the communication between the east and the west, a large number of English borrowing words entered Eastern Asian languages. In turn, there has been also many Eastern Asian languages loanwords entering English. China and Japan are both main countries in the East Asian cultural circle, and much of Japanese words come from Chinese, so we can find many similarities of Chinese and Japanese. However, the different features of Chineseborrowings and Japaneseborrowings in English can also be found. Since China has surpassed Japan and become the second-biggest economy at the end of 2010, the study has become more meaningful, for it will be of great help to linguistic and cultural communication.Therefore,this paper discusses the theme which former studies have hardly referred to, comparing the Englishborrowings from Japan and China, concluding their amounts, frequency of use, word-classes, subjects, the way of borrowing, and changes in pronounce.

Ⅱ. Literature Review

In the study of Japanese loanwords, Canons Japanese series (1981, 1982, 1984, 1994, 1995) has compiled a detailed corpus for us. From his in-depth and comprehensive research,Japanese borrowing words has been described according to their geographical, historical, variant forms and other phonological or graphemic considerations, word formation and other grammatical information, and the words places in general international English.In his latest study I can find, he showed us words usingwholly English elements but truly Japanese borrowings, which have filled a semantic gap in the existing English lexicon.From a six-month survey of two popular American magazines, Christopher P. Carman retrieved 29 contemporary borrowing of Japanese loanwords and analyzed them in terms of category, morphology, and the ability of coming into common English in 1991.Based on the Oxford dictionary, Schun Doi (2014) studied the naturalization process of Japanese foreign words.

In the study of Chineseloanwords,Cannon(1988) provides a list of 196 Chinese loanwords which enjoy general acceptance in English, based on different desk-dictionaries, and later studies the Sociolinguistic implications.Fromhis list, Moody(1996) compares the Chinese etymons with the borrowed form and determines the source or transmission language of each lexical borrowing. Isabel(2008) studies the Chinese loanwords in the OED. On top of that, Chinese researchers also have a strong presence in this regard.Donnson Chen (1992) made a classification of Chinese loanwords and points out three dialect origins. In 1998, Chang Junyue summed up the general rules of the changes of Chinese borrowing words in English, and Lin Lunlun and Chen li(2000) classified those words by the dialects. Ruan Jizhi(2002) analyzed several naming methods of things from China in English.Huang Yanjie focused on the cultural background, investigated the Chinese borrowings in English from a diachronic perspective. MAO Donghui (2006), Gu Juhua (2006), Xin Wen, Liu Jing, Dong Tong (2012), all have made summaries of history, characteristics or other aspects of Chinese borrowing words.

In the past half century, the historical origin and transformation characteristics of Japanese borrowing words and Chinese borrowings are well studied and summarized. But as we can see, previous studies have focused solely on borrowing words from Japaneseorfrom Chinese, and studied them separately. There is almost no comparative study between them. Therefore,this paper discusses this vacuum to try to make some contribution to fill up this niche.

Ⅲ. Contrastive Analyses of Chinese and Japanese Loanwords

1.The Number of Chinese and Japanese Loanwords According to Date. The number of Chinese and Japanese loanwords cannot be so accurate, as different dictionaries have different standard. This paper mainly studies the Chinese and Japanese loanwords in the Oxford English Dictionary online, also known as the OED. The dictionary contains 259Chinese loanwords and 525 Japanese loanword, and their timeline results can be seen in the following graph.

Figure 1 The number of English words borrowed from Chinese according to date (the OED, 2018)

Figure 2 The number of English words borrowed from Japaneseaccording to date(the OED, 2018)

The first borrowing words from Chinese (China, 1555) and Japanese are both in the 16th century. The first Japanese loanword was in 1577, but the second one appears in the 17th century. In the first half of the 17th century, there was a small peak of 20, but later it reduces into 4. In the first half of the 18th century, there is another peak, as many as 44, and in the second half of the 18th century it reduces to 1.As for Chinese loanwords, there are 4 in the 16th century (China, kiack, li, litch) and in the 17th century the number continues increasing with little fluctuation. We choose 500 years as a time period, from the first half of the 17th century to the second half of the 18th century, the number of Chinese loanwords is 3, 13, 17, 14. In general, before the 19th century, the amount of Japanese loanwords is larger than Chinese loanwords, with the number of 91 and 51. And the time of Japanese borrowings to English is concentrated, while the Chinese loanwords are relatively averaged from a large time span.

In the 19th century, the number of borrowing words of both languages shows an explosive growth. In the first half of the 19th century, there were only 21 Japanese, but in the second half century it rises steeply to 182.Because of the similarity of history and geographic location, the initial contact with English is at roughly the same time. The different characteristics of the growth of the two borrowings may be related to the politics of the two countries.For the reasons why Japanese loanwords are more than Chinese loanwords, I have found four main points. First of all, the communication between China and the UK is limited, mainly about trade. Secondly, Japan is active for the modernization and China is passive. Thirdly, the syllable of Japanese is simple, and easy to express in English. Finally, a lot of Japanese words are still used nowadays, with little change over time, but Chinese itself has changed greatly with time going by, so the early-time Chinese loanwords have already died and been replaced by new words.

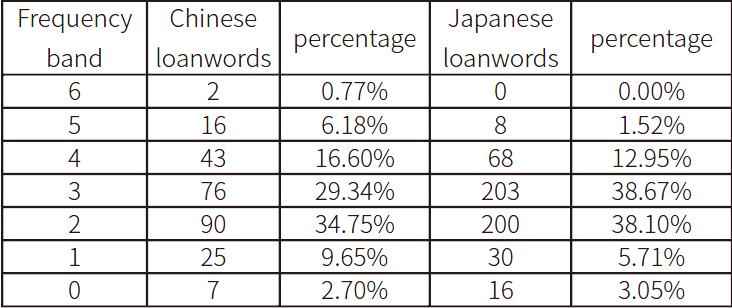

2.The Frequency of Chinese and JapaneseLoanwords. Table 1 The frequency of Chinese and Japanese loanwords(the OED, 2018)

Frequency band Chinese

loanwords percentage Japanese

loanwords percentage

6 2 0.77% 0 0.00%

5 16 6.18% 8 1.52%

4 43 16.60% 68 12.95%

3 76 29.34% 203 38.67%

2 90 34.75% 200 38.10%

1 25 9.65% 30 5.71%

0 7 2.70% 16 3.05%

From the table above we can see, there are 61 high-frequency words (frequency band 4 or above) in Chinese loanwords, accounting for 23.56%, and 76 in Japanese loanwords, accounting for 14.48%. Although the Chineses one is more, the proportion of low-frequency words (frequency band 1 or below, or can be named as obsolete words) is also higher.

3.The Word-class of Chinese and Japanese Loanwords. In terms of the part of speech, most of those loanwords are nouns, only a few of them are adjectives, and these adjectives are almost also nouns. Besides, verbs and exclamations can also be found.

Table 2 Number of Chinese and Japanese loanwords which are not nouns (the OED, 2018)

adjective interjection noun phrase verb

Chinese 16 4 254 1 2

Japanese 18 4 517 0 1

The Japanese loanwords that are not nouns are as follows.

sayonara, Showa, Meiji, mu, Nanga, nembutsu, ninja, Nippon, Nipponese, Nipponian, Nipponize, Nipponized, kainic, kamikaze, ah so, Ainu, banzai, gaijin, Heian, ibotenic, janken.

These 21 words make up 4% of the total.And in these 21 words, words which are not both an adjective and a noun are as follows.

mu (n.and int.), Nipponian (adj.), Nipponize (v.), Nipponized (adj.), kainic (adj.), ah so (int.), banzai (int.), janken (n. and int.).

These 8 words make up 1.52% of the total.The Chinese loanwords that are not nouns are as follows.

Ang moh, bohea, China, Hokkien, kiasu, Miao, Miaotse, Mien, Min, Ming, Nung, pongee, Qin, Qing, Song, Yao, aiyah, aiyoh, ganbei, wah, no can do, pung.

These 22 words make up 8.49% of the total.And In these 35 words, words which are not both an adjective and a noun are as follows.

aiyah (int.), aiyoh (int.), ganbei(int., n., and v.), wah (int.), no can do (phr.), pung(v.)

These 6 words make up 2.2% of the total.

From the above data, it can be seen that the composition of part of speech of Chinese loanwords is more complicated.

4.The Subjects of Chinese and Japanese Loanwords. Table 3 The subjects of Chinese and Japanese loanwords (the OED, 2018)

Subject Chinese Japanese

Agriculture and Horticulture 3 13

Arts 32 49

Consumables 26 47

Crafts and Trades 31 39

Drug use 4 0

Economics and Commerce 10 15

History 7 6

Law 1 3

Manufacturing and Industry 2 8

Military 5 27

Organizations 1 1

Politics 7 5

Religion and Belief 17 36

Sciences 22 63

Social Sciences 1 0

Sport and Leisure 15 84

Technology 6 15

Transport 2 4

Education 0 4

From the table of the subjects that Chinese and Japanese loanwords are in, we can find that the numbers of military, religion and belief, sciences, sport and Leisure and technology have big difference.And Chinese loanwords have none about education, while Japanese loanwords have none about drug use and social science, which may imply the cultural, economic and political differences between the two countries.

5. The Ways of Borrowing. By the ways in which Chinese loanwords are produced, Chinese loanwords can be briefly fused into three categories:calques (or loan translations), transliterations, and loanblends.

Calque itself embraces two components: free translation and literal translation. Free Translation refers to the way of creating words according to the things themselves, regardless of the original Chinese words. literal translation means translating according to the literal meaning of Chinese, like winter melon and paper tiger(1836).

In most Chinese papers, these words are considered as Chinese borrowings, but most of them are not considered to be loanwords in some English papers, or be uniformly treated as borrowings.According to Isabel study (2008), The OED provides 36 loan translations from Chinese. But these words cannot be found under the category of Chinese origin.

Loanblends are loanwords that adding English affixes to Chinese transliterated words. Chopstick(1615) can be sen as the most assimilated loanblend in the modern English. In Chinese and in ‘pigeon-English chop means ‘quick; so the English Seamen in the 17th century added ‘sticks after it and created the word Chopstick. (the OED, 2018) but so as calque, most of the loanblends are not be seen as the Chinese loanwords by the OED.

The main part of Chinese loanwords consists of transliteration words. Those transliterated word made way into English chiefly come from five dialects, Beijing Mandarin, Cantonese, Hokkien, Wu dialects, and some of the minority languages(Lin&Chen, 2000).In the 17th and 18th century, coastal areas traded more with Britain, so many Chinese words in Cantonese, Fujian dialects and Wu dialects were borrowed into English (Huang, 2005). Most of these borrowings in modern English vocabulary are about trade, food and goods. Like Litchi (1588), longan(1655),kumquat ( or cumquat,1699).Beijing mandarin loanwords are mainly Dynasty, place names, fruits and vegetables, animals, and proper nouns. For example, Tang(1669), Yang(1671), Tien (the Deity, heaven, 1613), kai shu (a script, 1876).For the tea trade in Fujian has been booming during the 18th to the 20th century, names of different kinds of tea have been borrowed in English. For instance, tea(1655), bohea(1704), pekoe(1713), congou(1725), oolong(1845), souchong(1761). In addition to this, ketchup also comes from Hokkien. It first appears in English in the 17th century, referring to a type of sauce and introduced to Britain by British travellers, traders, and colonists. From the late 19th century tomato ketchup became the most popular form (the OED).Two Tibetan words are fairly familiar in English, one is lama (Tibetan blama), used in an English translation of martinis Conquest of China in 1654, another is yak (from Tibetan gyak), recorded first at 1799 by Samuel Turner (Serjeantson,1935). Besides, Panchen(1763) and mani(1818) can also be concluded in this category.

Compared with the complex composition of Chinese loanwords, the composition of Japanese loanwords is very simple. Due to the simple pronunciation of Japanese, almost all of them are transliterated. Even the kanji words in Japanese come into English by pronunciation. There are also loan translations of Japanese. But just like those loan translations of Chinese, these words are not accepted by the mainstream, and can hardly be found under the words of Japanese origin in the OED. Whats more,Japanese dialects are not as many as Chinese dialects and Japanese doesnt change much over time. So Japanese loanwords in English are much moreclear than that of Chinese.

Japanese can be divided into wago words, kanji words, and loanwords. Wago words are words that have Japanese own origin. This kind of words are most about things and traditional culture. For example, kimono(1886), kabuki(1899), sushi(1893), miso(1615), Mikado(1727).Kanji words refer to words derived from Chinese. It is worth noting that many Chinese loanwords are first transmitted to Japan and then borrowed to English by Japanese. Many studies on Chinese loanwords classify them into Chinese loanwords, but I think they should be classifiedinto Japanese loanwords, because their pronunciation comes from Japanese, and they are trulyJapanese invention. Examples of this kind of loanwords are nanga(1910), soy(1696), zaikai(1968), ryokan(1914).Loanwords in Japanese are absorbed from foreign languages written as katakana, whichhave been translated into Japanese and integrated into Japanese vocabulary, some of which also known as heji English. These words were reintroduced into English and became Japanese loanwords in English. For example,tempo (Japanese borrowed from Italian, 1860), karaoke(1977).

6.Changes in Pronunciation and Spelling. The pronunciation of Chinese loanwords is very different from that of Chinese pinyin. Besides the complexity of dialects and the differences in phonetic spelling, some featurescan be summarized,changes in stress,loss of tone andsubstitution of phonemes. Here I refer to Chang Junyues findings (1998). When English lacks the original pronunciation of Chinese borrowing words, it will replace them by similar morphemes.

Japanese loanwords are also slightly changed in spelling, small but not negligible.According to the research of Liu Haixia(2009), there can befour situations: omission of long tone,(koji, 1878), ‘gusinto‘x(moxa,1675), ‘ninto‘m(kombu,1844), and some modifications according to English pronunciation(tycoon, 1875).

Ⅳ. Results / Findings

In number, English borrows more words from Japanese than Chinese. However,in terms of the word-class, Japaneseloanwords are not as rich as Chineseloanwords. High frequency words of Japanese loanwords are also less than that of Chinese. The differences in the categories of the two loanwords reflect the differences between the two countries in political, economy and culture. In borrowing methods, due to the complexity of Chinese history, numerous dialects, and the corresponding vacancy in English pronunciation, Chinese loanwords show a different complexity from Japanese. Rules of pronunciation of Chinese loanwordsarealso not as clear as that of Japanese.

Ⅴ. Conclusion

The differences in number and subjects of Chinese and Japanese loanwords in English reflect the gap between China and Japan in cultural export. As the worlds second largest economy, China needs to pay more attention to the synchronous development of culture, making thesoft power match with thehard power.

By borrowing words, we can not only see the differences between the two languages, but also realizethe differences between the two countries in history, culture, economy and politics, as well as the gap in comprehensive strength. Therefore, it is of great significance to strengthen the comparative study of loanwords, both for linguistics and for the overall development of the country.

References:

[1]Cannon, G. (1981). Japanese borrowings in English. American Speech,56(3), 190-206.

[2]Cannon, G. (1988). Chinese borrowings in English. American Speech,63(1), 3-33.

[3]Cannon, G. (1994). Recent Japanese borrowings into English. American Speech,69(4), 373-397.

[4]Carman, C. P. (2017). Japanese loanwords in English. Journal of Uoeh,13, 217-226.

[5]Chen, D. (1992). English borrowings from Chinese. 外國语(5), 60-64.

[6]Doi, S. (2014). The naturalisation process of the Japanese loanwords found in the. English Studies,95(6), 674-699.

[7]Isabel, D. L. C. C. (2008). Chinese loanwords in the OED. Studia Anglica Posnaniensia International Review of English Studies, 44.

[8]Li-Li, L. I. (2015). A tentative study of Chinese loanwords in the oxford English dictionary. 海外英语(14).

[9]Moody, A. J. (1996). Transmission languages and source languages of Chinese borrowings in English. American Speech,71(4), 405.

[10]常骏跃.英语中汉语借用成分语音、语法特征变化分析[J].外语与外语教学,1998(5):20-22.

- 基于小组合作的线上线下混合式教学研究

- 数据结构课程中面试式教学模式探索与实践

- 基于案例驱动的教学在《Java程序设计》课程中的实施与探索

- 线上教学改革探索

- 《进制的相互转换》信息化教学设计

- 基于C#课程的信息化教学方法研究

- 新建本科院校学生自主学习能力实证研究

- 虚拟现实技术在“大学计算机基础”课程中应用

- 面向自主学习的虚拟实验体系构建探索

- 基于在线开放课程线上线下混合式“金课”建设的探索与应用

- 高校计算机应用技术专业课程体系构建

- 《计算机维护技术》课程教学改革的分析

- 中外合作办学电气专业质量保障体系研究

- 翻转课堂在中职学生电教员培训中的教学设计模式研究

- 基于超星学习通的智慧课堂教学模式的构建与实践

- 5G背景下应用型本科高校大学生“双创”能力提升路径的创新教学研究

- 新工科背景下面向虚拟仿真实训的计算机网络工程实验教学探索

- 如何培养中职计算机专业学生的自主学习能力

- “互联网+”背景下高职计算机网络课程教学模式创新探究

- 基于OBE的《光传送网技术》课程教学研究

- “互联网+”背景下的大学英语课程体系构建

- 当代大学生对网络教育平台的认知情况调查

- 长文档编辑在现代信息技术教学中的应用

- “互联网+”背景下高等院校教学管理数字一体化建设

- 基于线上线下混合式学习通信原理课程教学研究与实践

- mismeshing

- mismetre

- misnarrate

- misnarrated

- misnarrates

- misnarrating

- misnavigate

- misnavigated

- misnavigates

- misnavigating

- misnavigation

- misnavigations

- misnomer

- misnomered

- misnomers

- mis-numbered

- misnumbered

- misnumbering

- misnumbers

- misobservance

- misoccupied

- misoccupies

- misoccupy

- misoccupying

- misogynist

- 翻衾倒枕

- 翻覆

- 翻覆搜求

- 翻覆无常

- 翻觔头

- 翻觔斗

- 翻论

- 翻词

- 翻译

- 翻译书籍

- 翻译人员

- 翻译介绍

- 翻译佛经的僧侣

- 翻译和写作

- 翻译和刊载

- 翻译和询问

- 翻译并刻印

- 翻译并校勘

- 翻译并注解

- 翻译并解说

- 翻译并解释

- 翻译方法

- 翻译片

- 翻译界

- 翻译的佛经