重温五十载教育技术研究:基于《英国教育技术期刊》的内容分析

[澳]梅丽莎·邦德 [德]奥拉夫·扎瓦克奇-里克特 [新西兰]马克·尼克尔斯

【摘 要】

本文对《英国教育技术期刊》1970年至2018年第3期刊发的1,777篇研究论文的标题和摘要进行内容分析,反思过去50年教育技术研究。本研究采用Leximancer这种文本挖掘工具分析每一个10年所出现的主要概念和主题,并把它們与《计算机与教育》和《英国教育技术期刊》同期被引率最高的文章的主要概念和主题进行比较。过去50年《英国教育技术期刊》常见主题包括远程教育教与学的发展、教学设计的出现、实践者与学习设计者之间的误解、职前和在职教师教育以及教育工作者和学生接受技术的问题(使用技术的信心、教育工作者和学生的技术技能和机构没有提供培训和融合所需的空间和时间等方面的支持)。本文还针对今后的研究提出建议,包括研究教育工作者专业发展的其他模式和进一步探索理论与政策的作用。

【关键词】? 教育技术;研究;内容分析;在线学习;远程教育;开放学习;文本挖掘;研究趋势

【中图分类号】? G420? ? ? ?【文献标识码】? B? ? ? ?【文章编号】? 1009-458x(2020)1-0001-22

导读:刚刚迎来50华诞的《英国教育技术期刊》(British Journal of Educational Technology,BJET)是一本历史悠久、在学界享有崇高声望的国际学术期刊,所发表的学术成果在很大程度上反映了本领域学术研究和实践探索的发展变化。这篇文章是该刊纪念50华诞专辑的重头戏,原文围绕四个研究问题,内容非常丰富,篇幅庞大。作者根据我的要求对文章进行浓缩,仅聚焦第一个研究问题,并承蒙该刊出版商Wiley和期刊所属机构英国教育技术协会(British Educational Research Association)的慷慨应允,翻译成中文发表于本刊“国际论坛”。

我之所以要求作者仅聚焦一个研究问题——“从1970年至2018年,BJET的载文呈现哪些研究趋势和内容?这些趋势和内容又是如何发展变化的?”除了篇幅因素外,更主要是为了与本刊另外两篇分别对《远程教育》(Distance Education)①和《计算机与教育》②(Computer & Education)进行同类研究的文章呼应。这三份期刊都是久负盛名的SSCI教育技术类国际期刊,因此这三篇文章能够相互印证、相互补充,勾画出过去几十年教育技术领域的发展概貌。

文章首先对BJET的历史和针对该刊的同类研究做一个简单回顾,然后介绍样本采集情况和所用研究方法以及局限。研究方法与上面提到的另外两项研究一样,这里不赘述。“研究结果和讨论”是本文的主要内容,包括六个方面:

(1)BJET载文概况(1970—2018年)

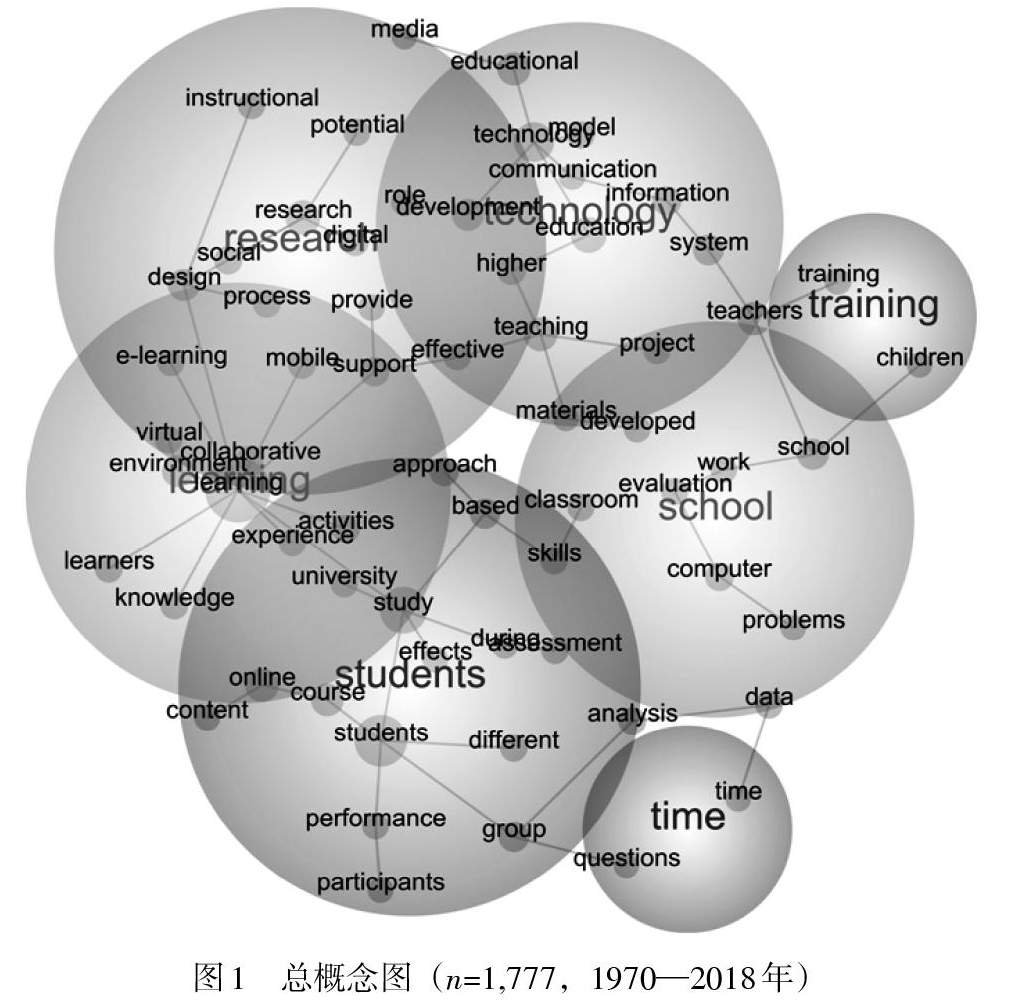

50年所发表的1,777篇研究论文呈现7个主要主题,其中重要性遥遥领先的是“学习”和“学生”——“learning(学习)被直接提到2,466次(相对计数100%),随后是students(学生)(73%)、technology(技术)(37%)、research(研究)(28%)、school(学校)(21%)、training(培训)(10%)和time(时间)(7%)”。一般人可能觉得BJET是一份技术性很强的期刊,所以这点似乎有些出乎意料,但却与另外两份期刊的分析结果相印证,比如它们也是《远程教育》[“……创刊35年来……1,005次直接提到education(教育)(相对计数100%)、learning(学习)(63%)、students(学生)(53%)、research(研究)(36%)、interaction(交互)(6%)”①]和《计算机与教育》[“……过去40年(1976—2016年)……9,432次直接提到student(学生)(相对计数100%)、learning(学习)(93%)、school(学校)(84%)、tool(工具)(58%)、computer(计算机)(52%)、analysis(分析)(36%)和programming(编程)(9%)”②]一直以来的重要主题。另一方面,policy(政策)和theory(理论)却不是其主要主题,从内容分析情况看BJET注重实践——技术支持教与学,在一定程度上轻视理论发展(这是其不足),至于“政策”研究的不足,是整个教育技术研究领域的通病。③④⑤

(2)多媒体学习和开放大学(1970—1979年)

BJET第一个10年恰逢以英国开放大学为旗帜的世界开放大学运动风起云涌之时,而“教育技术处于发展阶段”,一切都有待于探索。因此,“开放大学和基于媒体的课程设计的发展”“解决教育问题还是带来新的教育问题?”“教师专业发展”成为这个时期的新兴研究内容。

(3)从视听向基于计算机的学习的转变(1980—1989年)

虽然诸如无线电广播、电视、录像磁带和电话这些“传统”技术仍然是这个时期的研究对象,但是微电脑和多媒体数据库等“新”技术开始在教育中得到应用,如何通过教学设计促进技术融合、提高学习质量自然是一个值得关注的领域;distance(远程)作为一个概念也首次出现在概念图上,“这反映‘远程学习和‘远程教育作为‘新添的教育行业术语在研究文献中得到认可”。因此,“改进远程教育教与学”“(技术)融合和实施的问题”“教学设计的出现”成为这个时期的新兴研究内容。

(4)远程教育的发展和交互式学习的兴起(1990—1999年)

“这个时期迎来了开放灵活学习新时代。”远程教育得益于教育技术的新发展以及基于协作和建构主义的新方法和科学的教学设计,“交互式被寄予厚望”,而新技术和新方法也给教师带来新挑战,教师专业发展再次引起关注。因此,“远程教育的发展”“交互式多媒体、课件和软件开发”“教师专业发展和技术”成为这个时期的新兴研究内容。

(5)学校在线协作学习和信息通信技术的实施和设计(2000—2009年)

这个时期,distance(远程)这个概念退居幕后,在线和混合式学习如火如荼,因特网和信息通信技术的教育潜能被广泛看好,教学设计再次被寄予厚望。因此,“在线和混合式学习”“因特网和信息通信技术在学校的角色”“教学设计和背景因素考虑”成为这个时期的新兴研究内容。

(6)学习分析和移动协作学习(2010—2018年)

learning(学习)和students(学生)是这个时期最重要的主题,比以往任何时期都重要。学习分析“能够加深我们对学生学习过程的了解”“帮助我们了解学习设计对学生成功的影响”“直接支持学生学习”;协作则是21世纪关键能力之一,因此如何开展在线环境下的协作引起广泛关注;协作工具与移动技术相得益彰,极具教育能供性。因此,“学习分析的出现”“高等教育的在线协作”“移动学习和新工具的研发”成为这个时期的新兴研究内容。

综观50年的研究成果,有些问题一直存在,是技术与教育融合、技术促进教与学的妨碍因素,包括实践者与学习设计者的脱节、缺乏有效教师专业发展、技术实际应用水平低、缺乏信息技术支持服务等。这些是各国面对的共性问题,应引起我们的高度重视。

仔细品味BJET过去50年发表的研究成果,感触良多,但限于篇幅,无法一一展开。相信读者会有自己的体会,能从中得到与自己的研究与实践相关的启示。

最后,衷心感谢三位作者、Wiley出版集团和英国教育技术协会对本刊的支持!(肖俊洪)

一、引言

《英国教育技术期刊》(The British Journal of Educational Technology,BJET)是教育技术领域历史最悠久、最负声望的期刊之一,今年(2019年——译注)迎来50华诞。这一重要里程碑促使其编辑团队和本文作者思考BJET对教育技术领域的贡献。本文旨在通过内容分析全面回顾过去50年教育技术研究的发展,从BJET的载文研究技术对教与学的影响。学界越来越重视研究各研究领域的发展(Weismayer & Pezenka, 2017),教育技术领域也不例外(Bodily, Leary, & West, 2019; Bond & Buntins, 2018; Rushby & Seabrook, 2008; Tamim, Bernard, Borokhovski, Abrami, & Schmid, 2011)。BJET是教育技术领域最有影响力的期刊之一(Ritzhaupt, Sessums, & Johnson, 2012),我们希望通过分析其过去50年载文,加深对这个领域发展的了解。虽然此前已经有研究者分析BJET作者成分和内容,包括以BJET为唯一研究对象(Hawkridge, 1999; Latchem, 2006; Mott, Ward, Miller, Price, & West, 2012)和把BJET与其他教育技术期刊进行比较(如:Baydas, Kucuk, Yilmaz, Aydemir, & Goktas, 2015; Bodily, et al., 2019; Hsu, et al., 2012; Hsu, Hung, & Ching, 2013),但是本研究能够更加深入分析过去50年载文的主要概念和主题,有助于我们更好地了解这本期刊。

(一)BJET简史

创刊于1970年的BJET是英国全国教育技术理事会(National Council for Educational Technology)官方期刊,旨在发表与教育技术相关的各种题材的研究成果。该刊从一开始便努力做到突出国际性,国际化与近年出现的包容性和创新一起成为其主要主题之一(Girvan, Hennessy, Mavrikis, Price, & Winters, 2017)。创刊编委会由一名主编尼克·拉什比(Nick Rushby)和14名顾问编辑组成,除了英国人以外还包括美国人、荷兰人、瑞典人和以色列人。创刊以来,先后有来自加拿大、保加利亚、澳大利亚、新西兰、中国、日本、牙买加、意大利、巴西、俄罗斯和斯洛文尼亚等国家的学者加入其编委会。此外,还有分布在环太平洋(后来称为“亚太地区”)、南非、中国、印度的一批通信编辑在不同时期服务该刊。的确,该刊现在可以自豪地声称大多数读者、审稿人和投稿人来自英国以外(Girvan, et al., 2017)。目前,其编辑团队有5名成员,编委会有30名成员,还有一个由来自世界各地区9名专家组成的国际顾问委员会。BJET专刊主编和作者也反映其国际化的愿望(见表1)。

(二)针对BJET的已有研究

此前已经有一些围绕BJET的文献研究和内容分析。霍克里奇(Hawkridge, 1999)是纪念该刊创刊30周年之作,回顾1970年创刊号的文章,分析该期“内容广泛”(p. 299)的研究,并研究BJET创刊30年来编辑政策的变化。他认为高涨的教育成本和便利的教育技术会使政府和教育机构更加重视教育技术,但是在教学设计和建构主义理论的应用上还需要下更大力气。霍克里奇的希望后来得以实现。莱切姆(Latchem, 2006)对BJET的内容分析显示,2000—2005年发表的理论探索性文章中一半聚焦新技术和教学设计问题,而且大多数是针对高等教育的研究(另見Hsu, et al., 2012);总体研究趋势朝着学生驱动而非教师引领的方向发展。这一点也体现在更大范围的教育献中(如Bond & Buntins, 2018; Marín, Duart, Galvis, & Zawacki-Richter, 2018; Zawacki-Richter & Latchem, 2018)。莱切姆呼吁要更加重视对适合职场学习和发展的教育技术的研究,继续重视理论研究,更加关注政府和机构的政策和程序。

有研究(Baydas, et al., 2015)比较BJET和《教育技术研究与发展》(Educational Technology Research and Development)2000—2014年发表的文章,结果发现2008年之后BJET有关在线学习主题的文章增长17%,学习环境主题的文章增长14%。另一项研究(Mott, et al., 2012)也发现2001—2010年BJET在线论坛文章呈现增长态势,最近十年远程学习主题文章也略有增长,教学设计研究的重点则转向博客、维基和慕课(Bodily, et al., 2019)。有研究者(Hsu, et al., 2013)分析六本SSCI教育技术期刊,发现2000—2009年三个最常见主题群分别是宏观视角下的技术融合、学习交互和协作学习,以及教学设计,而韦斯特和博勒普(West & Borup, 2014)调查了十份教学设计和技术期刊2001—2010年发表的文章,发现BJET最主要的主题包括远程教育、交流、与认知相关的内容、态度等。BJET的主编们也在编者按语中分析来稿的常见主题(Rushby, 2010; 2011)。采用文本挖掘工具对其载文进行内容分析,这是否能得到与上述相吻合的主题呢?这点会很有趣。因此,本研究拟回答以下研究问题:

从1970年至2018年,BJET的载文呈现哪些研究趋势和内容?这些趋势和内容又是如何发展变化的?

二、样本和方法

(一)1970—2018年BJET的载文

本研究分析了BJET从1970年至2018年第3期全部研究论文(n=1,777)。书评、编者按语和争鸣之类的文章不予纳入。表2是每一个10年的载文数量,2001年该刊从每年4期改为每年5期,2004年增加至6期。我们对样本以每10年为单位分成五个子数据集:1970—1979年(n=202)、1980—1989年(n=184)、1990—1999年(n=177)、2000—2009年(n=502)和2010—2018年(n=712)。考虑到撰写本文的实际时间,样本仅收录至2018年第3期。必须指出,科学网(Web of Science)数据库和BJET网站有不一致之处,有些文章没有被科学网索引。此外,有些文章在BJET网站和科学网都被列为研究论文,然而下载后发现它们实则是争鸣(如:Sosabowski, Herson, & Lloyd, 1999)。研究者在开展此类研究时必须注意此类问题。

(二)计算机辅助内容分析

本研究采用Leximancer软件进行内容分析。过去十年,借助软件分析大量数据,特别是用于发现学术期刊自身或比较不同期刊的主要概念和趋势,这种情况发展很快(Zawacki-Richter & Latchem, 2018)。研究发现计算机辅助内容分析是描绘一个研究领域概况的合适方法(Fisk, Cherney, Hornsey, & Smith, 2012),既省时省费还能减少人为偏见(Krippendorff, 2013)。采用这种方法分析教育技术领域期刊的研究包括对《计算机与教育》(Computers & Education,CAE)(Zawacki-Richter & Latchem, 2018)、《澳大拉西亚教育技术期刊》(Australasian Journal of Educational Technology)(Bond, 2018; Bond & Buntins, 2018)和《教育技术》(Edutec)(Marín, Zawacki-Richter, Pérez Garcías, & Salinas, 2017)的分析。這种方法也被用于心理学(如:Cretchley, Rooney, & Gallois, 2010)、商学(如:Liesch, H?kanson, McGaughey, Middleton, & Cretchley, 2011)和传播学(如:Lin & Lee, 2012)等领域期刊的内容分析。

鉴于本研究的目的,我们从BJET网站和科学网采集1970—2018年第3期的所有研究论文(n=1,777)的摘要和标题,转换成Excel的CSV文件,输入文本挖掘工具Leximancer。诸如use、used和using以及paper和results等词汇被删除掉,单复数词汇则被合并(如student和students)。Leximancer自动识别两个句子中有意义的概念和主题,生成显示所发现的概念的频率和关联度的概念图(主题大小默认值50%)(Smith & Humphreys, 2006)。研究发现Leximancer效果优于简单计算词频(如词云图)工具,因为它还考虑语义和语言复杂性(Nunez-Mir, Iannone, Pijanowski, Kong, & Fei, 2016)。必须承认摘要可能会漏掉一些重要信息(Curran, 2016),但是通过分析摘要和标题了解一个领域的发展是合适的,因为它们的“词汇密度通常很高,突出文章的核心内容”(Cretchley, et al., 2010, p. 319)。同类研究还包括《远程教育》(Distance Education)(1980—2014年)(Zawacki-Richter & Naidu, 2016)、《国际开放和分布式学习研究评论》(International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning)(2000—2015年)(Zawacki-Richter, et al., 2017)和CAE(创刊40周年)(Zawacki-Richter & Latchem, 2018)等期刊。

Leximancer自动生成包含主要主题的概念图,如computer(计算机)或student(学生)。主题数量根据数据集词汇的频率和关联度自动产生,因此不同概念图的主题或话题数量可能各不相同。为了分析这些概念图,作者们深入了解相关背景和话题,对概念图和相应数据进行比对,在此基础上解读所生成的概念图(Harwood, et al., 2015)。具体步骤包括在每一个10年的数据库搜索主要概念和主题的词汇和短语,讨论涌现的主要主题和概念,然后通读相关文章以更深入理解这些主题和概念。第一作者分析概念图、阅读文章、撰写分析报告,但是新兴主题和概念路径则是全体作者讨论的结果。我们在分析2010—2018年概念图时还请教了一位学习设计专家。我们随后借助Publish or Perish软件(Harzing, 2007)把概念图的质性内容分析结果与每一个10年被引率最高的文章(详见英文原文附录F)进行比较。

(三)局限

虽然Leximancer减少人为偏见(Krippendorff, 2013),而且与人工采用扎根理论方法相比结果稳定(Harwood, et al., 2015),但是Leximancer也颇具争议。有研究者(Leydesdorff, 1997)认为文本、题材和作者的不同会导致词汇的语义不同,这种不确定性可能导致一个词在一个数据集中意義的不稳定。然而,也有研究者(Courtial, 1998)提出不同意见,指出“词汇只不过被用于显示文本之间的连接,不是用来表情达意的语言单位”,共词分析“计算网络模式,因此能够显示一个词在某个阶段出现在共词网络的中心或战略位置”(Courtial, 1998, p.98)。因此,本研究拟结合计算机辅助分析和人工内容分析(Weismayer & Pezenka, 2017),举例说明“概念路径”所示的主要新兴研究主题,以说明每一个概念图所包含主题的代表性。

虽然BJET久负盛名,但是必须指出它只不过是了解教育技术领域的一个英语窗口,而且任何期刊都受到编辑团队、审稿人和拨款机构影响(Goldenberg & Grigel, 1991)。同样重要的一点是,过去15年每年的载文量显著多于早期,这会影响到反映概况全貌的概念图,导致它更加突出近年载文的主题。

三、研究结果和讨论

(一)BJET载文概况(1970—2018年)

图1显示BJET过去50年载文(n=1,777)的主要主题和研究领域。主题概括显示,learning(学习)被直接提到2,466次(相对计数100%),随后是students(学生)(73%)、technology(技术)(37%)、research(研究)(28%)、school(学校)(21%)、training(培训)(10%)和time(时间)(7%)。由此可见,BJET的文章并非专门聚焦技术,而是主要涉及与技术相关的学习过程(详见英文原文附录A)。出乎意料的是,policy(政策)和theory(理论)没有出现在图1总概念图上,这说明有必要继续呼吁进一步加强本领域批判性和理论研究(比如Casta?eda & Selwyn, 2018; Latchem, 2006)。的确,研究发现很多教育章缺乏指导性理论或概念框架(Antonenko, 2015; Karabulut-Ilgu, Jaramillo Cherrez, & Jahren, 2018)。在过去18个月,这已经成为BJET编辑团队的一个重要关注点(Hennessy, Girvan, Mavrikis, Price, & Winters, 2018),包括在英国开放大学(the Open University)组织各种活动以及计划2019年以“发展教育技术研究和实践的批判性和理论方法”为主题的专刊,由吉尔·詹姆森(Jill Jameson)教授担任客座主编。

概念图显示BJET发表的研究主要是技术支持有效教与学[见概念路径learning(学习)-support(支持)-effective(有效)-teaching(教学)-higher(高等级)-education(教育)-technology(技术)-educational(教育的)-media(媒体)],尤其是在线协作学习环境和中小学环境下。“(它所发表的文章考虑)……和报告教育技术干预和创新,而且不仅是大专院校的干预和创新,还包括正式和开放学校教育、在家教育、职业教育和培训、职场培训和专业发展等方面的干预和创新。这(对BJET这样一份期刊来说)极其重要”(Latchem, 2014, p.6)。Leximancer的分析显示BJET过去50年载文强调中小学,school(学校)出现511次。相比之下,higher education(高等教育)只是221次,university(大学)则是193次。这种趋势也体现在每一个10年的载文中。然而,如果把higher education和university的次数加在一起,我们发现2000—2009年和2010—2018年这两个10年的载文主要围绕高等教育,school(学校)在2000—2009年仅出现73次,莱切姆(Latchem, 2006)的研究也证明这是BJET在2000-2005年载文的趋势。training(培训)出现238次,然而主要是指专门技能的培训(比如社交媒体技能,如Benson & Morgan, 2016)或教师专业发展(20世纪70和80年代通常用“培训”指教师专业发展),而不是继续教育环境下的培训。

为了进一步了解BJET载文的研究背景并把它跟另一份主要教育技术期刊CAE放在一起讨论,我们在BJET和CAE所发表的中小学、高等教育和培训领域的文章中进一步检索,分析这些词出现的次数。有学者对CAE进行类似于本研究的分析(Zawacki-Richter & Latchem, 2018)。这两份期刊在学界都享有很高声望,也是SSCI仅有的办刊历史40年以上的教育技术期刊。然而,它们有各自的特色和重点关注领域。为了控制载文量不同这个因素,我们根据每一份期刊载文量对出现次数进行标准化处理,即相关词语在每一篇文章的平均出现次数。分析结果显示(见表3),虽然BJET的确比较强调中小学环境(平均每篇出现0.44次school),但是它对高等教育的重视几乎不相上下(平均每篇出现0.40次higher education)。相比之下,CAE更加强调中小学环境(平均每篇出现0.51次school),而对高等教育的重视程度则明显较低(平均每篇出现0.26次higher education)。至于专业发展和培训,相关研究在两份期刊均属少数。

BJET第一个10年的载文恰好是20世纪70年代英国开放大学和紧随其后其他远程开放教学大学(如加拿大阿萨巴斯卡大学[Athabasca University]和德国远程大学[FernUniversit?t])的创办时期。但是,在过去20年,远程开放学习渐渐不再为BJET文章所关注,取而代之的是因特网的发展以及在线和协作学习等概念(见英文原文附录H)。CAE研究主题一直都是聚焦于计算机在教与学中的应用,但是,如同BJET一样,计算机或教育技术被看作是一种工具,研究的目的是如何发挥数字媒体给在线环境下协作学习带来的潜能和机会。

如下文所示,BJET载文中涌现的主要研究主题(见英文原文附录G)包括开放大学的发展和变化、新技术的发展和与各种教育环境的融合、采用新技术的问题(包括教师专业发展、合适的技术和教学法的调整)、远程教育(从基于印刷学习材料到无线电广播和电视、在线学习和开放教育资源的发展)和教学设计(从早期技术的潜能到在线学习环境和学习分析)。

(二)多媒体学习和开放大学(1970—1979年)

第一个10年载文包括科研论文,还包括书评、点评、会议论文和尚处于初期规划阶段或正在进行中的项目的报告(因为此时“教育技术处于发展阶段”[BJET Editors, 1970年, p.8])。这些项目报告旨在引发辩论,促进学界就如何最有效把理论付诸实践进行交流,以及如何利用教育技术加强教与学。

图2概念图呈现1970—1979年这个时期载文(n=202)涉及的主要研究领域。主题概括显示educational(教育的)被直接提到66次(相对计数100%),随后是teaching(教学)(92%)、research(研究)(67%)、course(课程)(47%)、development(发展)(39%)、media(媒体)(35%)和analysis(分析)(21%)。这个时期被引率最高的文章(见英文原文附录F)的主题与此吻合。

1. 开放大学和基于媒体的课程设计的发展

BJET的创刊恰逢英国开放大学开始招生。1971年1月英国开放大学在全国招收近25,000名学生(Lewis, 1971b)。英国开放大学给年满21岁但不符合大学入学资格的成年人提供在家业余远程学习的机会。一开始,只有4个系列的课程供选择(文科、社会科学、数学或理科),学生每4周~6周会收到学习材料包(Scupham, 1970)。由于新设课程数量的增加,教师承受很大压力开发“编写得好”和“有吸引力的”书面学习材料,同时还要制作电视和广播节目[见概念路径course(课程)-work(工作)-project(项目)-teaching(教学)-Open University(开放大学)-materials(材料)]。但是,当时对于如何有效开展这些工作的研究不多(Bates & Gallagher, 1976; Lewis, 1971a)。因此,这个时期的很多文章报告了英国开放大学开展的项目的情况,旨在研究如何才能使媒体最有效提高学习效果[见概念路径Open University (开放大学)-teaching(教学)-learning(学习)-methods(方法)-information(信息)-media(媒体)]。研究涉及电视和广播教学(如:Gallagher & Marshall, 1975; Scupham, 1970)、电话会议(如:Turok, 1975)以及媒体的选择和与课程融合的最佳实践(如:Bates & Pugh, 1975; Connors, 1972)。

2. 解决教育问题还是带来新的教育问题

技术进入大中小学主流预计会产生重大影响,预示着将迎来教育设计新时代,以解决“世界教育危机”(Chadwick, 1973, p. 80)[见概念路径development(发展)-instructional(教学的)-system(系统)-education(教育)-problems(问题)和problems(问题)-education(教育)-system(系统)-world(世界)-educational(教育的)-technology(技术)]。但是,这个时期的研究显示教育技术没有发挥人们热盼的作用(如:Thornbury, 1979)。虽然有些文章呈现使用教育技术的好处(如:Chadwick, 1973; Tidhar, 1973),但是绝大多数研究根据BJET创刊之初制订的范围(BJET Editors, 1970),力图讨论和了解使用新技术和新方法碰到的问题。这些问题包括学校购买的硬件找不到合适的软件、教师没有接受使用技术的培训,致使设备被闲置在仓库(Featherstone, 1970),或教师几乎没有时间学习新技术方法或开发新资源(Atherton, 1979)。各学科的教学设计没有对它们的差别给予应有考虑(Harris, 1976)或没有针对新技术的使用而调整教学方法(Farrugia, 1975)。使用教育技术进行课程评价时经常没有恰当地纳入学生对课程的看法,以帮助课程设计者了解如何修改和改进内容和传送方式(Bates & Gallagher, 1976)。尽管如此,学界对于“教育技术(会)成为教育研究和发展一个专门分支”(Hawkridge, 1976, p. 28)并“开始从一门伪科学向正当的研究领域发展”(Mansfield & Nunan, 1978, p.175)仍然持平静、乐观的态度。

3. 教师专业发展

这个时期的文章承认和强调持续教师专业发展的重要性[见概念路径classroom(课堂)-teacher(教师)-development(发展)-instructional(教学的)-system(系统)-training(培训)-computer(计算机)]。由于初期教师教育没有机会接触教育技术,很多教师在完全没有准备好迎接新的“技术时代”的情况下登上讲台,而且他们常常没有获得足够教学豁免时间(release time),以便学习和练习所需技能(Featherstone, 1970; Foxall, 1972)。正因如此,英国全国教育技术理事会强调必须培训教师“使用各种各样视听设备……这是(教师专业发展)必不可少的内容”,为他们登上讲台做好准备(National Council of Educational Technology, 1971, p.103)。然而,第一個10年后期的文章(如:Collier, 1977; Moss, 1979)涉及学界对技术进步与新的教师教育课程融合的怀疑、谨慎和无知,以及在职教师专业发展机会的缺失或教师不愿意参加这些活动(如:Elton, 1979; Teather & Collingwood, 1978; Wilkes, 1977)。

(三)从视听向基于计算机的学习的转变(1980—1989年)

虽然20世纪80年代的很多文章仍然主要涉及视听设备(如无线电广播、电视、录像磁带和电话)在教育中的使用(Okwudishu & Klasek, 1986; Reid & Champness, 1983),但是研究已经开始转向评价教育技术融合的情况(如:Harris & Bailey, 1982; Prosser, 1984)和引进微电脑(如:Goldes, 1984; Menis, 1987)、多媒体数据库(如:Barker & Yeates, 1981)和资源中心(如:Gibson, 1981)。

图3呈现BJET这个时期文章(n=184)涉及的主要研究领域。主题概括显示这些文章聚焦learning(学习),出现113次(相对计数100%),紧接着分别是educational(教育的)(73%)、design(设计)(28%)、training(培训)(27%)、problems(问题)(26%)和schools(学校)(21%)。值得注意的是,distance(远程)(19%)首次出现在概念图上,这反映“远程学习”和“远程教育”作为“新添的教育行业术语”在研究文献中得到认可(Halliwell, 1987, p. 5),与1980年创刊的《远程教育》不无关系(Zawacki-Richter & Naidu, 2016)。这个时期除了见证远程教育研究的增加之外,很多文章讨论和调查与技术融合和实施相关的广泛问题,越来越关注教学设计,而且如同这个时期被引率最高的文章(见英文原文附录F)所反映的,更加强调对以学生为中心的学习方法的了解和探索(如:Morgan, Taylor, & Gibbs, 1982)[见概念路径students(学生)-learning(学习)-approach(方法)]。

1. 改进远程教育教与学

远程教育渐渐“作为一种合法、可供选择的教学方式被接受,而不是针对不能参加全日制校园教育人士提出的一種低劣教学方法”(Harper & Kember, 1986, p.221)。这些文章聚焦各国远程教育项目和创新,特别是那些幅员辽阔的国家,包括澳大利亚(如:Stanford & Imrie, 1981)、加拿大(如:Peruniak, 1984)和中国(如:McCormick, 1985)。有学者讨论了师生关系的重要性(Store & Armstrong, 1981)[见概念路径education(教育)-distance(远程)-students(学生)-learning(学习)-teaching(教学)-methods(方法)],强调学习材料必须能够提供有效反馈和嵌入自我评价练习。对于很多发展中国家来讲,当时无线电广播节目是最有成本效益和可行的“现代”远程学习方法(如:Halliwell, 1987)。但是,由于无线电广播的收听质量差、播出时间不合适以及缺乏维修昂贵设备的资金,这些节目只能算是取得部分成功。因此,在第二个10年即将结束时,学界的注意力转向如何提升远程学习研究上,比如马兰(Marland, 1989)建议采用一种新的社会—人类学和认知的混合范式。

2. 融合和实施的问题

20世纪80年代的文章阐述了与使用新媒体[见概念路径problems(问题)-technology(技术)-educational(教育的)-television(电视)]和开发与维护合适教与学材料[见概念路径problems(问题)-technology(技术)-educational(教育的)-materials(材料)-development(开发)-curriculum(课程计划)]等相关的各种问题。虽然教育部门和机构热衷于采用新技术,比如澳大利亚租借视频项目(Australian Loan Video Programme)(Hosie, 1985),但是资金常常很快“沉没”到昂贵设备上,没有花足够时间培训教师,不重视教学设计,服务课程需要的水平有限,也没有考虑今后如何维护这些设备(如:Jenningswray & Wellington, 1985)。

熟悉诸如APL、BASIC和FORTRAN这些编程语言以编辑计算机辅助教学材料也被认为是教师面临的一个问题(如:Barker & Singh, 1982, 1983),因为“其复杂性和不寻常性会使新手气馁和灰心”(Goldes, 1984, p.162)。有一组文章阐述学习技术在高等教育机构中的角色(如:Riley, 1984a, 1984b, 1984c),讨论“课堂教师由于不了解学习技术人员能给他们提供什么帮助而经常倍感受挫”的问题(Collier, 1983, p.146)。也有研究者对于中小学如何管理新多媒体资源(如:Gibson, 1981)和教师觉得计算机“未来可能最终取代他们”(Menis, 1987, p.98)等问题表示关切。因此,研究者呼吁教师要不断参与研究,“不再需要证明媒体的作用,但必须改进媒体”(Moore, Wilson, & Armistead, 1986, p.192)——这是学界的认识。

3. 教学设计的出现

第二个10年初期,研究者对于“新媒体没有对教育机构的实践产生显著影响”深感沮丧(White, 1980, p.170)。他们为此建议开辟一个新研究分支,这个分支有共同语言并“贯穿于整个领域”(Romiszowski, 1982, p.17)。我们必须能够理解教育技术专家如何选择、组织和传播知识。这点至关重要(如:White, 1980),虽然克尔(Kerr, 1983)认为没有任何一种教学设计会提供准确决策的处方。学界普遍认为课程目的和目标以及学习过程是设计过程的核心(如:Kerr, 1983; Romiszowski, 1981),尤其是对于高等教育而言(Cowan & Harding, 1986)。但是中小学不一定非这样不可(Ibebassey, 1988),其教师经常首先考虑的是他们有什么材料。因此,研究也聚焦如何提高学习材料质量,提升学习结果[见概念路径problems(问题)-technology(技术)-educational(教育的)-materials(材料)-development(开发)-curriculum(课程计划)],比如可以使用文字处理(如:Duchastel, 1983; Kember & Kemp, 1989)和多媒体工作站(如:Barker, 1987),或教师学习在微输入程序上打字(Wheeler, 1980),加快制作过程。

(四)远程教育的发展和交互式学习的兴起(1990—1999年)

20世纪90年代学界号召教育技术专家要欢迎其他人加入这个行列并向有兴趣提升技能者提供培训(Willis, 1990),而不是排除他们,同时要使教育技术走向现代化(Hawkridge, 1990),使这个领域能够继续发展。图4呈现1990—1999年BJET文章(n=177)的主要概念。learning(学习)再次成为研究焦点,被直接提到122次(相对计数100%),随后是school(学校)(38%)、educational(教育的)(35%)、course(课程)(30%)、design(设计)(19%)、software(软件)(16%)和courseware(课件)(15%)。television(电视)这个概念在概念图上消失了,computer(计算机)的重要性也不如从前,但仍然与students(学生)、teaching(教学)和learning(学习)紧密联系在一起。相比之下,software(软件)和courseware(课件)现在成为关注中心,交互式多媒体的潜能,尤其是在中小学环境,也成为关注中心。这点在这个时期被引率最高的文章中也得到反映(见英文原文附录F)。

1. 远程教育的发展

这个时期迎来了开放灵活学习新时代,“出现各种各样的方法全方位支持学习过程”(Laurillard, 1995, p.182),政府则提供财政支持促进国际合作(比如欧盟,见Van den Branden & Lambert, 1999)。虽然远程教育继续使用电视这种手段(如:Boulet, Boudreault, & Guerette, 1998; Idrus, 1993),但是技术的进步使交互式媒体的使用越来越多[见概念路径distance(远程)-course(课程)-learning(学习)-students(学生)-study(学习)-skills(技能)-technology(技术)和training(培训)-interactive(交互式)-multimedia(多媒体)-educational(教育的)-development(发展)],包括计算机会议和在线辅导(如:Rowntree, 1995)和用电子邮件向学生提供视频反馈(如:Inglis, 1998)。在采用越来越具协作性技术的同时,协作和建构主义方法也越来越受到重视(Dillon & Gunawardena, 1992; Idrus, 1993; Laurillard, 1995; Rowntree, 1995)。远程教育的教学设计也成为研究焦点[见概念路径distance(远程)-course(课程)-learning(学习)-instructional(教学的)-design(设计)],负责教学技术的人则必须成为“设计师”或“建筑师”(Ely, 1999, p.308),而不仅仅是“技术员”。英国开放大学的讨论集中在设计团队应该如何齐心协力提高教学材料质量上(如:Melton, 1990; Thomas, Carswell, Price, & Petre, 1998),也要关注资源制作国际合作中碰到的困难(Hawkridge, 1993)。这个时期的文章继续强调向学生提供多种机会自我评价和反思的重要性(如:Inglis, 1998),呼吁模块作者接受教学设计和发展、学习理论以及媒体选择和融合这些方面的培训(如:Hashim, 1999)。

2. 交互式多媒体、课件和软件开发

当时人们“对多媒体学习的兴趣激增”(Plowman, 1996, p.93)[见概念路径potential(潜能)-video(视频)-interactive(交互式)-multimedia(多媒体)-educational(教育的)-development(开发)],虽然有些研究者也对此进行降温,比如有研究者警告说并非任何学习都能够仅靠电子材料进行(Min, 1994)。交互式被寄予厚望,但是它不是“教育的灵丹妙药”(Aldrich, Rogers, & Scaife, 1998, p.324)。交互式视频被当成一个重大进步而受到热捧(Spencer, 1991),有针对高等教育的研究(如:Jones, 1993),主要是针对中小学环境的研究(如:Beishuizen & Vanputten, 1990; Kuboni, 1992; Yildiz & Atkins, 1996)[见概念路径school(学校)-classroom(课堂)-interactive(交互式)-video(视频)-potential(潜能)]。从1985年到1987年,英国政府花了200多万英鎊在96所中小学试点“学校交互式视频”(Interactive Video in Schools)项目(Norris, Davies, & Beattie, 1990)。虽然起初大家热情高涨,项目试点历时15个月,但是,教师们发现没有足够时间在学生中使用学习资源包,也没有信心使用新技术开展教学试验。虽然交互式视频材料取得一些积极效果,但是这些材料与国家课程大纲没有关联(Plowman & Chambers, 1994),而且需要更具针对性和指导(Yildiz & Atkins, 1996)。

以CD-ROM形式呈现的交互式多媒体[见概念路径courseware(课件)-development(开发)-educational(教育)-multimedia(多媒体)-software(软件)]被誉为“比任何其他技术创新更能够直接影响教育方式和学校以及职场应该强调哪些类型的技能”(Perzylo, 1993, p.192)。但是,人们也承认交互式多媒体必须有有效教学法与之相配(Laurillard, 1995)和能从认知上吸引学生(Barron, 1998),才能促使深度学习发生。通过因特网发布课件(如:Trathen & Sajeev, 1996)也对教学设计产生影响,课件的开发则需要投入巨资(Canale & Wills, 1995; Friedler & Shabo, 1991)。课程设计的计划和灵活性被视为至关重要(如:Foster, 1993; Nikolova & Collis, 1998),必须在更大程度上考虑文化因素(Hawkridge, 1993; Van den Branden & Lambert, 1999)。这些文章还认为教学材料应该提供多种学习路径,支持各种学习风格和方法(Wild & Quinn, 1998),以及支持信息技术知识和技能薄弱的学生(Pitt, 1996)。但是,必须承认虽然有些研究继续考虑学习风格(Newton, 2015),然而20世纪90年代以来学习风格备受质疑(如:Coffield, Moseley, Hall, & Ecclestone, 2004; Newton & Miah, 2017)。

3. 教师专业发展和技术

在这个时期,通过因特网和电子邮件向学生提供学习支持已经成为可能(Pitt, 1996)[见概念路径support(支持)-learning(学习)-students(学生)-based(基于)-teaching(教学)-computer(计算机)],教师也有机会使用课件生成器(Friedler & Shabo, 1991)、插件和诸如JAVA的编程语言开发基于网络的培训(Barron, 1998)。随着交互式技术的发展,人们意识到职前和在职教师使用信息技术方面存在不足(Wild & Quinn, 1998),某种程度上是因为他们对使用信息技术缺乏信心(Gardner & McNally, 1995; Norris, et al., 1990)。有研究者建议增加如何使用技术的培训和指导(Beishuizen & Vanputten, 1990)[见概念路径teachers(教师)-technology(技术)-skills(技能)-information(信息)-system(系统)-different(不同)和 teachers(教师)-technology(技术)-school(学校)-classroom(课堂)-training(培训)],随之而来的是开发了基于现实生活场景、以计算机为媒介的培训和交互式视频内容(Gardner & McNally, 1995; McEvoy & McConkey, 1991),包括教师使用技术。的确,英国和澳大利亚这些国家职前教师教育发生重大变化,学生多达80%的初期培训将在学校进行(Hacker & Sova, 1998),因此越来越需要有随时可以获取的合适学习材料。

(五)学校在线协作学习和信息通信技术的实施和设计(2000—2009年)

与前期各阶段相比,这个时期的文章数量呈几何数增长(n=502)。图5显示system(系统)作为一个概念出现在概念图上,learning(学习)继续成为最主要的概念,出现709次(相对计数100%),随后是students(学生)(69%)、technology(技术)(34%)、system(系统)(22%)、knowledge(知识)(16%)和ICT(信息通信技术)(13%)。这个时期被引率最高的文章(见英文原文附录F)也反映这些主题,有3篇在线学习文章、2篇移动学习文章和3篇协作性章。图5概念图与另一项研究的结果相互补充,该研究(Hsu, et al., 2013)发现这个时期三个最主要的主题群是:宏观视角下的技术融合、学习交互和协作学习以及教学设计。

1. 在线和混合式学习

这个时期之初,随着在线和混合式学习模式越来越流行[见概念路径online(在线)-students(学生)-study(学习)-learning(学习)-e-learning],有研究者宣称“我们所认识的远程教育将消失”(Carr-Chellman & Duchastel,2000, p. 231)。distance(远程)这个概念的消失反映了这种观点。这个时期的研究旨在了解学生在线学习体验(如:Hudson, Owen, & van Veen, 2006; Shin & Chan, 2004)[见概念路径online(在线)-students(学生)-study(学习)-learning(学习)-context(背景)],包括使用电子档案袋(如:Mason, Pegler, & Weller, 2004)、常规在线测验和考试(如:Angus & Watson, 2009)和在线终结性考核任务(如:Marriott, 2009)等技术开展在线考核[见概念路径online(在线)-students(学生)-assessment(考核)]。这些文章还研究加大在线讨论参与度是否会影响学生整体成绩(如:Davies & Graff, 2005)和参与课外活动情况(如:Leese, 2009)[见概念路径online(在线)-students(学生)-cognitive(认知)-analysis(分析)],研究结果令人鼓舞,促使人们进一步研究在线社区的发展和影响(如:Allan & Lewis, 2006; Murphy, 2004)。诸如Active Worlds(Dickey, 2005)和Second Life(Bell, 2009; Edirisingha, Nie, Pluciennik, & Young, 2009; Salmon, 2009)这些3D虚拟世界的潜能也成为研究内容[见概念路径online(在线)-students(学生)-study(学习)-approach(方法)-interactive(交互式)和collaborative(協作)-learning (学习)-environment(环境)]。然而,有研究者(Warburton, 2009)警告必须更深入了解数字和文化素养以及如何管理虚拟身份、提高设计技能,只有这样3D虚拟世界才有可能最有效地用于提高教与学效果。

2. 因特网和信息通信技术在学校的角色

随着人们越来越认识到信息通信技术素养对未来的重要性,这个时期的文章探索信息通信技术和因特网在学校的使用[见概念路径development(发展)-educational(教育的)-technology(技术)-school(学校)-children(儿童)],涉及各种国际背景,比如约旦(Tawalbeh, 2001)、印度(Mitra & Rana, 2001)、新加坡(Shabajee, McBride, Steer, & Reynolds, 2006)、土耳其(Ozdemir & Kilic, 2007)、中国(Ho, 2007)和加拿大(Gibson & Oberg, 2004)。英国中小学生使用计算机尤为令人感兴趣,研究发现虽然学生对信息通信技术有积极看法(Selwyn & Bullon, 2000),政府也投入可观资金,但是学校对于计算机的使用和因特网接入有诸多限制,从而影响技术发挥促进教与学的潜能(Selwyn, Potter, & Cranmer, 2009)。这也可能是因为教师认为自己在技术上不如学生(Madden, Ford, Miller, & Levy, 2005),没有时间参加信息通信技术专业发展活动(Williams, Coles, Wilson, Richardson, & Tuson, 2000),或学校没有提供信息技术支持服务(Lai & Pratt, 2004)。有些文章还研究信息通信技术如何能够帮助有学习困难的学生(如Lewis, Trushell, & Woods, 2005; Lynch, Fawcett, & Nicolson, 2000),以及诸如交互式白板这些新工具(Wall, Higgins, & Smith, 2005; Wood & Ashfield, 2008)如何能够促进学习、引发学习。

3. 教学设计和环境因素考虑

到了21世纪第一个10年,“教学设计(已经)发展成为一门艺术性科学”(Crawford, 2004, p.414),作为把学习理论应用于优化学习的一种形式,其重要性得到进一步承认(Mukhopadhyay & Parhar, 2001)。在线环境的教学设计越来越被认为有自己的媒介,向更加体现以学生为中心和基于活动的设计方向发展(Carr-Chellman & Duchastel, 2000),研究者提出一些教学模式(如:Alonso, Lopez, Manrique, & Vines, 2005),以得益于理论研究和应用理论(比如自我决定理论,见 Cheng & Yeh, 2009),进一步帮助教师和教学设计者创建以学习者为中心的环境[见概念路径instructional(教学的)-design(设计)-evaluation(评价),instructional(教学的)-design(设计)-based(基于)-system(系统)-computer(计算机)-model(模式)和individual(个人)-students(学生)-study(学习)-learning(学习)-environment(环境)]。

(六)学习分析和移动协作学习(2010—2018年)

图6显示当前10年(截至2018年49卷3期)BJET文章(n=712)的主要主题和概念,从中可见通过教育技术的使用,学生的学习过程继续得到强调,即如同20年前学者所预见的,“对学习者的敏感性进一步提高”(Ely, 1999, p.309)。事实上,learning(学习)(相对计数100%)和students(学生)(75%)是这个时期的重要主题,比前10年还要重要,分别出现1,460和1,101次。technology(技术)(35%)紧随其之后,然后是analysis(分析)(14%)、performance(表现)(11%)和model(模式)(10%)。

从图6可见,BJET是一份专注实践的期刊,文章内容涉及中小学和大学学生使用技术的体验以及各种工具如何能够提升和影响教学实践。这些方面也体现在这个时期被引率最高的文章中(见英文原文附录F)。自从2000年以来,BJET出版了13期专刊;专刊能使期刊集中反映当前研究趋势(Zawacki-Richter & Naidu, 2016),有助于影响这个时期的新兴研究主题。analysis(分析)这个主题的出现反映我们采用更加依靠数据引领的方法理解技术促进学习的过程,这是2015年46卷2期专刊“教师引领的研究与学习设计”的中心。distance(远程)这个概念又一次从概念图上消失了,online(在线)、virtual(虚拟)、mobile(移动)、digital(数字化)和e-learning则依然出现在概念图上,这应验了卡尔-查尔曼和杜查斯特尔(Carr-Chellman & Duchastel, 2000)的预言。

1. 学习分析的出现

在这个时期,数据分析作为一个重要发展领域而出现,尤其是针对数据分析如何能够加深我们对学生学习过程的了解(如:Jesus Rodriguez-Triana, Martinez-Mones, Asensio-Perez, & Dimitriadis, 2015)[见概念路径analysis(分析)-assessment(考核)-learners(学习者)-learning(学习)-process(过程)]。从宏观层面看,有围绕使用大数据帮助我们了解学习设计对学生成功的影响的研究(如:Toetenel & Rienties, 2016)[见概念路径instructional(教学的)-design(设计)-learning(学习)-learners(學习者)-assessment(考核)-analysis(分析)]。然而,也有涉及微观层面的研究,调查分析技术的应用(如:Lambropoulos, Faulkner, & Culwin, 2012)。技术对考核设计的影响(Bennett, Dawson, Bearman, Molloy, & Boud, 2017)和考核分析技术[见概念路径learners(学习者)-assessment(考核)-analysis(分析)]也出现于文献中(Ellis, 2013),以学习者为导向的考核能使学生更深入自我反思,也给循证教学评价提供机会(如:Nix & Wyllie, 2011; Whitworth & Wright, 2015)。从这些文章的广度和分析层次可以看出,我们必须探索基于数据的理解和实践方法,才能使实践得到发展(如:McKenney & Mor, 2015)。后来的文章还研究学习分析如何能够直接支持学生学习(如:Daley, Hillaire, & Sutherland, 2016; González-Marcos, Alba-Elías, & Ordieres-Meré, 2016)。很多文章讨论机构使用学生数据的道德和隐私问题(如:Pardo & Siemens, 2014),也警告人们不能只依靠数据科学和计算方法(Veletsianos, Collier, & Schneider, 2015)。

2. 高等教育的在线协作

协作被列为21世纪关键能力之一(Ananiadou & Claro, 2009)。这个时期的文章非常重视在线环境下的协作[见概念路径online(在线)-students(学生)-study(学习)-learning(学习)-collaborative(协作)],尤其是在高等教育领域(如James, 2014)[见概念路径higher(高等级)-education(教育)-learning(学习)-collaborative(协作)]。这个时期初期的文章继续关注如何利用3D世界支持协作学习[见概念路径collaborative(协作)-learning(学习)-environment(环境)-virtual(虚拟)]和通过模拟达到深度学习(如Dalgarno & Lee, 2010)。虽然研究表明协作和合作对于知识建构(Myll?ri, ?hlberg, & Dillon, 2010)和有意义的学习(Yang, Yeh, & Wong, 2010)很重要,在线学习的协作不会自动发生(Zhao, Sullivan, & Mellenius, 2014),还可能增加学生压力(Jung, Kudo, & Choi, 2012)。如何通过发展有凝聚力的社区以最有效促进深度学习和提高学习成效是这个时期的研究重点,比如基于探究社区框架(Community of Inquiry Framework)(Akyol & Garrison, 2011)和有效交互模型(Effective Interaction Model)(Calvani, Fini, Molino, & Ranieri, 2010)开发课程,以及研发诸如社交临场量表(Social Presence Scale)的工具(Kim, 2011)。然而,也有文章指出在线协作环境下教师对“技术的使用尚未达到最理想状态”的情况继续存在(ONeill, Scott, & Conboy, 2011, p. 945),教学设计必须继续考虑文化因素(Jung, et al., 2012)。

3. 移动学习和新工具的研发

这个时期的研究继续强调技术在教与学方面的潜能(如:Ngambi, 2013)[见概念路径potential(潜能)-technology(技术)-teaching(教学)-learning(学习)],调查各种技术的融合情况,比如移动学习[见概念路径mobile(移动)-technology(技术)-potential(潜能)]和协作工具[见概念路径collaborative(协作)-learning(学习)-teaching(教学)-technology(技术)-tools(工具)]。初期的文章研究如何使用社交媒体促进学生学习,比如使用Twitter促进意义建构(如:Charitonos, Blake, Scanlon, & Jones, 2012)和学习投入(如:Junco, Elavsky, & Heiberger, 2013),以及如何利用社交媒体扩展专业发展学习网络(如:Pimmer, Linxen, & Groehbiel, 2012)。近年的文章则强调使用移动信息应用程序促进社会交互(如:Sun, Lin, Wu, Zhou, & Luo, 2018)以及游戏在提高儿童对STEM课程学习兴趣方面的作用(如:Herodotou, 2018)。然而,教育工作者和学生对于Web 2.0和协作工具的使用一直有所担心(James, 2014),移动学习给学生带来心理上的挑战也不容忽视(Terras & Ramsay, 2012)。如果要保证技术可持续和无缝的融合,那么必须给教育工作者和学生提供更多技术和教学上的支持(Tondeur, et al., 2017),可以通过持续实践社区鼓励提供这些支持(Cochrane, 2014)。

四、结束语、建议和今后研究

本文希望通过分析BJET这份久负盛名学术期刊创刊以来的载文内容了解过去50年教育技术研究的发展。分析结果印证了此前针对BJET同类研究的结果(Baydas, et al., 2015; Hsu, et al., 2012; Hsu, et al., 2013; Latchem, 2006; Mott, et al., 2012)。BJET的文章从一开始便涉及广泛内容,鼓励批判性、坦率发表意见。有些主题贯穿于各个时期,包括实践者与学习设计者之间的误解和摩擦、由于各种原因缺乏有效的教师职前和在职专业发展、师生对某些技术的采用率持续低下、学校没有提供信息技术支持服务、教师缺乏专业发展时间和师生信息技术技能水平一直不高。其他主题清楚表明BJET是一份能够反映实践领域发展的期刊,比如远程教育、社会建构主义、学习设计和学习分析,学习总是被摆在第一位,而不是技术。

尤其是教育工作者的技术专业发展这个主题过去50年反复出现,各级机构一直在努力减少教育工作者的教学或行政管理任务,使他们有更多时间参加专业发展;这些机构也一直在努力提供足够的职前教师技术教育,虽然一些国家在20世纪90年代相关政策发生变化,增加了职前教师到学校实习的时间,因此有更多实际接触技术的机会。大规模专业发展活动可能是有助于减轻机构负担的一种方案(如:Laurillard, et al., 2018),持续实践社区也不失为一种解决方案(如:Cochrane, 2014)。然而,这些方案可能并非所有教育工作者都能享受到或世界各地教育机构都能办到。因此,必须有其他方案可用于帮助教育工作者为技术与课堂成功融合做好准备、提供支持服务,尤其针对职前教师教育和中小学的方案。BJET过去10年这些方面的载文减少了。进一步加强研究者与其他机构(如中小学、博物馆等)之间的联系,鼓励教师和其他实践者参与研究和撰写研究论文,都可能进一步激发反思实践(Cober, et al., 2015)。有研究者指出,“主要利益相关者没有参与技术方案的设计可能会导致这些方案与学习者和实践者的日常问题或环境脱节,限制了干预措施的影响”(Perez-Sanagustin, et al., 2017, p. A12)。

受到本研究所采用的研究方法的启发,有一点特别建议,希望其他拟开展同类研究的作者注意,如果需要从文献数据库(比如科学网)提取数据,而且内容分析仅针对某一、两类文章(如实证研究),那么应该考虑与期刊网站和(或)文章的pfd文档进行比对。本研究发现科学网与BJET网站对文章类型的标识有不一致之处,BJET网站的标识与文章实际类型也有不一致的情况。

本研究也发现各时期概念图没有出现“政策”和“理论”这个问题。因此,今后的研究要通过分析载文类型和所用研究方法,进一步了解BJET来稿是如何随着时间推移发生变化的。理论发展和理论联系实际方面也需要继续开展研究(Casta?eda & Selwyn, 2018; Jameson special issue of BJET, forthcoming; Latchem, 2006),虽然这些方面因为以学习者为中心的在线环境的发展在21世纪得到更多重视。这点体现在相关研究(West & Borup, 2014)和本研究2010—2018年概念图出现的概念路径[framework(框架)-development(發展)-teachers(教师)-technology(技术)]中。过去50年,教育技术研究越来越重视反馈和自评在促进学生深度反思方面的作用,对学习分析技术的进一步研究表明学习分析具有深入揭示学习过程的潜能(如:Montgomery, et al., 2017),但尚需进一步研究其有效性(见S?nderlund, Hughes, & Smith, 2018)。

【开放数据、道德和利益冲突声明】本研究是ActiveLearn课题成果,获得德国教育和研究部(Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung)资助(拨款编号16DHL1007)。第三作者马克·尼克尔斯博士是BJBET编委会成员。

【鸣谢】衷心感谢英国开放大学学习设计主任杰拉尔德·埃文斯(Gerald Evans)分享其專业知识和德国奥尔登堡卡尔·冯·奥西茨基大学斯韦尼亚·贝登利耶(Svenja Bedenlier)博士的支持!

[参考文献]

Akyol, Z., & Garrison, D. R. (2011). Understanding cognitive presence in an online and blended community of inquiry: Assessing outcomes and processes for deep approaches to learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42(2), 233-250.

Aldrich, F., Rogers, Y., & Scaife, M. (1998). Getting to grips with “interactivity”: helping teachers assess the educational value of CD-ROMs. British Journal of Educational Technology, 29(4), 321-332.

Allan, B., & Lewis, D. (2006). The impact of membership of a virtual learning community on individual learning careers and professional identity. British Journal of Educational Technology, 37(6), 841-852.

Alonso, F., Lopez, G., Manrique, D., & Vines, J. M. (2005). An instructional model for web-based e-learning education with a blended learning process approach. British Journal of Educational Technology, 36(2), 217-235.

Ananiadou, K., & Claro, M. (2009). OECD Education Working Papers (Vol. 41).

Angus, S. D., & Watson, J. (2009). Does regular online testing enhance student learning in the numerical sciences? Robust evidence from a large data set. British Journal of Educational Technology, 40(2), 255-272.

Antonenko, P. D. (2015). The instrumental value of conceptual frameworks in educational technology research. Educational Technology Research and Development, 63(1), 53-71.

Atherton, R. (1979). Microcomputers, Secondary Education and Teacher Training. British Journal of Educational Technology, 10(3), 198-216.

Barker, P. G. (1987). A Practical Introduction to Authoring for Computer-Assisted Instruction. Part 8: multi-media CAL. British Journal of Educational Technology, 18(1), 25-40.

Barker, P. G., & Singh, R. (1982). Author languages for computer-based learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 13(3), 167-196.

Barker, P. G., & Singh, R. (1983). A practical introduction to authoring for computer-assisted instruction 2. British Journal of Educational Technology, 14(3), 174-200.

Barker, P. G., & Yeates, H. (1981). Problems associated with multi-media databases. British Journal of Educational Technology, 12(2), 158-175.

Barron, A. (1998). Designing Web-based training. British Journal of Educational Technology, 29(4), 355-370.

Bates, A., & Pugh, A. (1975). Designing Multi-Media Courses for Individualised Study: The Open University Model and its Relevance to Conventional Universities. British Journal of Educational Technology, 6(3), 46-56.

Bates, T., & Gallagher, M. (1976). The Development of Research in Broadcasting at the Open University. British Journal of Educational Technology, 7(1), 31-43.

Baydas, O., Kucuk, S., Yilmaz, R. M., Aydemir, M., & Goktas, Y. (2015). Educational technology research trends from 2002 to 2014. Scientometrics, 105(1), 709-725.

Beishuizen, M., & Vanputten, K. (1990). The use of videotaped broadcasts in interactive teaching. British Journal of Educational Technology, 21(2), 95-105.

Bell, D. (2009). Learning from Second Life. British Journal of Educational Technology, 40(3), 515-525.

Bennett, S., Dawson, P., Bearman, M., Molloy, E., & Boud, D. (2017). How technology shapes assessment design: Findings from a study of university teachers. British Journal of Educational Technology, 48(2), 672-682.

Benson, V., & Morgan, S. (2016). Social university challenge: Constructing pragmatic graduate competencies for social networking. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(3), 465-473.

BJET Editors. (1970). Editorial. British Journal of Educational Technology, 1(1), 7-8.

Bodily, R., Leary, H., & West, R. (2019). Research Trends in Instructional Design and Technology Journals. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(1), 64-79.

Bond, M. (2018). Helping doctoral students crack the publication code: An evaluation and content analysis of the Australasian Journal of Educational Technology. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 34(5), 167-181.

Bond, M., & Buntins, K. (2018). An analysis of the Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 2013-2017. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 34(4), 168-183.

Boulet, M. M., Boudreault, S., & Guerette, L. (1998). Effects of a television distance education course in computer science. British Journal of Educational Technology, 29(2), 101-111.

Calvani, A., Fini, A., Molino, M., & Ranieri, M. (2010). Visualizing and monitoring effective interactions in online collaborative groups. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(2), 213-226.

Canale, R., & Wills, S. (1995). Producing professional interactive multimedia - project management issues. British Journal of Educational Technology, 26(2), 84-93.

Carr-Chellman, A., & Duchastel, P. (2000). The ideal online course. British Journal of Educational Technology, 31(3), 229-241.

Casta?eda, L., & Selwyn, N. (2018). More than tools? Making sense of the ongoing digitizations of higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15(1), 211.

Chadwick, C. (1973). Educational Technology: Progress, Prospects and Comparisons. British Journal of Educational Technology, 4(2), 80-94.

Charitonos, K., Blake, C., Scanlon, E., & Jones, A. (2012). Museum learning via social and mobile technologies: (How) can online interactions enhance the visitor experience? British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(5), 802-819.

Cheng, Y.-C., & Yeh, H.-T. (2009). From concepts of motivation to its application in instructional design: Reconsidering motivation from an instructional design perspective. British Journal of Educational Technology, 40(4), 597-605.

Cober, R., Tan, E., Slotta, J., So, H-J., & K?nings, K. (2015). Teachers as participatory designers: two case studies with technology-enhanced learning environments. Instructional Science, 43, 203-228.

Cochrane, T. D. (2014). Critical success factors for transforming pedagogy with mobile Web 2.0. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(1), 65-82.

Coffield, F., Moseley, D., Hall, E., & Ecclestone, K. (2004). Learning styles and pedagogy in post-16 learning: A systematic and critical review. London: Learning and Skills Research Centre.

Collier, K. (1977). Educational Technology and the Curriculum of Teacher-Education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 8(1), 5-10.

Collier, K. (1983). Learning Technology Departments and Institutional Management Policy. British Journal of Educational Technology, 14(2), 143-151.

Connors, B. (1972). Testing Innovations in Course Design. British Journal of Educational Technology, 3(1), 48-52.

Courtial, J. (1998). Comments on Leydesdorffs Article. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 49(1), 98-99.

Cowan, J., & Harding, A. G. (1986). A logical model for curriculum development. British Journal of Educational Technology, 17(2), 103-109.

Crawford, C. (2004). Non-linear instructional design model: eternal, synergistic design and development. British Journal of Educational Technology, 35(4), 413-420.

Cretchley, J., Rooney, D., & Gallois, C. (2010). Mapping a 40-Year History With Leximancer: Themes and Concepts in the Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 41(3), 318-328.

Curran, F. C. (2016). The State of Abstracts in Educational Research. AERA Open, 2(3), 233285841665016.

Daley, S. G., Hillaire, G., & Sutherland, L. M. (2016). Beyond performance data: Improving student help seeking by collecting and displaying influential data in an online middle-school science curriculum. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(1), 121-134.

Gallagher, M., & Marshall, J. (1975). Broadcasting and the Need for Replay Facilities at the Open University. British Journal of Educational Technology, 6(3), 43-53.

Gardner, J., & McNally, H. (1995). Supporting school-based initial teacher training with interactive video. British Journal of Educational Technology, 26(1), 30-41.

Gibson, D. G. (1981). The development of resource centres in Scottish secondary schools. British Journal of Educational Technology, 12(1), 64-69.

Gibson, S., & Oberg, D. (2004). Visions and realities of Internet use in schools: Canadian perspectives. British Journal of Educational Technology, 35(5), 569-585.

Girvan, C., Hennessy, S., Mavrikis, M., Price, S., & Winters, N. (2017). BJET Editorial November 2016. British Journal of Educational Technology, 48(1), 3-6.

Goldenberg, S., & Grigel, F. (1991). Gender, science and methodological preferences. Social Science Information, 30(3), 429-443.

Goldes, H. (1984). User problems in interactive environments. British Journal of Educational Technology, 15(3), 161-175.

González-Marcos, A., Alba-Elías, F., & Ordieres-Meré, J. (2016). An analytical method for measuring competence in project management. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(6), 1324-1339.

Hacker, R., & Sova, B. (1998). Initial teacher education: a study of the efficacy of computer mediated courseware delivery in a partnership context. British Journal of Educational Technology, 29(4), 333-341.

Halliwell, J. (1987). Is Distance Education by Radio Outdated? A consideration of the outcome of an experiment in continuing medical education with rural health care workers in Jamaica. British Journal of Educational Technology, 18(1), 5-15.

Harper, G., & Kember, D. (1986). Approaches to Study of Distance Education Students. British Journal of Educational Technology, 17(3), 212-222.

Harris, D. (1976). Educational Technology at the Open University: A Short History of Achievement and Cancellation. British Journal of Educational Technology, 7(1), 43-53.

Harris, N. D. C., & Bailey, J. G. (1982). Conceptual Problems Associated with the Evaluation of Educational Technology Courses. British Journal of Educational Technology, 13(1), 4-14.

Harwood, I., Gapp, R. P., & Stewart, H. J. (2015). Cross-check for completeness: Exploring a novel use of leximancer in a grounded theory study. Qualitative Report, 20(7), 1029-1045.

Harzing, A. (2007). Publish or Perish. Retrieved from http://www.harzing.com/pop.htm

Hashim, Y. (1999). Are instructional design elements being used in module writing? British Journal of Educational Technology, 30(4), 341-358.

Hawkridge, D. (1976). Next Year, Jerusalem! The Rise of Educational Technology. British Journal of Educational Technology, 7(1), 7-30.

Hawkridge, D. (1990). Who is modernising educational technology? British Journal of Educational Technology, 21(3), 231-232.

Hawkridge, D. (1993). International coproduction of distance teaching courses. British Journal of Educational Technology, 24(1), 4-11.

Hawkridge, D. (1999). Thirty years on, BJET! and educational technology comes of age. British Journal of Educational Technology, 30(4), 293-304.

Hennessy, S., Girvan, C., Mavrikis, M., Price, S., & Winters, N. (2018). Editorial. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(1), 3-5.

Herodotou, C. (2018). Mobile games and science learning: A comparative study of 4 and 5 years old playing the game Angry Birds. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(1), 6-16.

Ho, W.-C. (2007). Students experiences with and preferences for using information technology in music learning in Shanghais secondary schools. British Journal of Educational Technology, 38(4), 699-714.

Hosie, P. J. (1985). A Window on the World. British Journal of Educational Technology, 16(2), 145-163.

Hsu, Y.-C., Ho, H., Tsai, C.-C., Hwang, G.-J., Chu, H.-C., Wang, C.-Y., & Chen, N.-S. (2012). Research Trends in Technology-based Learning from 2000 to 2009: A content Analysis of Publications in Selected Journals. Educational Technology & Society, 15(2), 354-370.

Hsu, Y.-C., Hung, J.-L., & Ching, Y.-H. (2013). Trends of educational technology research: more than a decade of international research in six SSCI-indexed refereed journals. Educational Technology Research and Development, 61(4), 685-705.

Hudson, B., Owen, D., & van Veen, K. (2006). Working on educational research methods with masters students in an international online learning community. British Journal of Educational Technology, 37(4), 577-603.

Ibebassey, G. S. (1988). How Nigerian teachers select instructional materials. British Journal of Educational Technology, 19(1), 17-27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.1988.tb00248.x

Idrus, R. (1993). Collaborative learning through teletutorials. British Journal of Educational Technology, 24(3), 179-184.

Inglis, A. (1998). Video email: a method of speeding up assignment feedback for visual arts subjects in distance education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 29(4), 343-354.

James, R. (2014). ICTs participatory potential in higher education collaborations: Reality or just talk. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(4), 557-570.

Jenningswray, Z., & Wellington, P. I. (1985). Educational Technology Utilization in Jamaicas Secondary School System: present problems and future prospects. British Journal of Educational Technology, 16(3), 169-183.

Jesus Rodriguez-Triana, M., Martinez-Mones, A., Asensio-Perez, J. I., & Dimitriadis, Y. (2015). Scripting and monitoring meet each other: Aligning learning analytics and learning design to support teachers in orchestrating CSCL situations. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(2, SI), 330-343.

Jones, B. (1993). Efficient use of interactive video with large groups. British Journal of Educational Technology, 24(3), 185-190.

Junco, R., Elavsky, C. M., & Heiberger, G. (2013). Putting twitter to the test: Assessing outcomes for student collaboration, engagement and success. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(2), 273-287.

Jung, I., Kudo, M., & Choi, S.-K. (2012). Stress in Japanese learners engaged in online collaborative learning in English. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(6), 1016-1029.

Karabulut-Ilgu, A., Jaramillo Cherrez, N., & Jahren, C. T. (2018). A systematic review of research on the flipped learning method in engineering education: Flipped Learning in Engineering Education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(3), 398-411.

Kember, D., & Kemp, N. (1989). Computer-aided publishing and open learning materials. British Journal of Educational Technology, 20(1), 11-26.

Kerr, S. T. (1983). Inside the black box - making design decisions for instruction. British Journal of Educational Technology, 14(1), 45-58.

Kim, J. (2011). Developing an instrument to measure social presence in distance higher education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42(5), 763-777.

Krippendorff, K. J. (2013). Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. Retrieved from https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/content-analysis/book234903

Kuboni, O. (1992). Designing instructional television for concept-learning in low-achieving pupils in Trinidad and Tobago. British Journal of Educational Technology, 23(2), 95-105.

Lai, K. W., & Pratt, K. (2004). Information and communication technology (ICT) in secondary schools: the role of the computer coordinator. British Journal of Educational Technology, 35(4), 461-475.

Lambropoulos, N., Faulkner, X., & Culwin, F. (2012). Supporting social awareness in collaborative e-learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(2), 295-306.

Latchem, C. (2006). Editorial: A content analysis of the British Journal of Educational Technology. British Journal of Educational Technology, 37(4), 503-511.

Latchem, C. (2014). BJET Editorial: Opening up the educational technology research agenda. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(1), 3-11.

Laurillard, D. (1995). Multimedia and the changing experience of the learner. British Journal of Educational Technology, 26(3), 179-189.

Smith, A., & Humphreys, M. S. (2006). Evaluation of unsupervised semantic mapping of natural language with Leximancer concept mapping. Behavior Research Methods, 38(2), 262-279.8

S?nderlund, A. L., Hughes, E. & Smith, J. (2018). The efficacy of learning analytics interventions in education: A systematic review. British Journal of Educational Technology.

Sosabowski, M. H., Herson, K., & Lloyd, A. W. (1999). Hurdles to successful implementation of “Learning Trees”. British Journal of Educational Technology, 30(1), 61-64.

Spencer, K. (1991). Modes, media and methods-The search for educational effectiveness. British Journal of Educational Technology, 22(1), 12-22.

Stanford, J. D., & Imrie, B. W. (1981). A Three-Stage Evaluation of a Distance Education Course. British Journal of Educational Technology, 12(3), 198-214.

Store, R. E., & Armstrong, J. D. (1981). Personalizing Feedback Between Teacher and Student in the Context of a Particular Model of Distance Teaching. British Journal of Educational Technology, 12(2), 140-157.

Sun, Z., Lin, C.-H., Wu, M., Zhou, J., & Luo, L. (2018). A tale of two communication tools: Discussion-forum and mobile instant-messaging apps in collaborative learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(2, SI), 248-261.

Tamim, R. M., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Abrami, P. C., & Schmid, R. F. (2011). What forty years of research says about the impact of technology on learning: A second-order meta-analysis and validation study. Review of Educational Research, 81(1), 4-28.

Tawalbeh, M. (2001). The policy and management of information technology in Jordanian schools. British Journal of Educational Technology, 32(2), 133-140.

Teather, D., & Collingwood, V. (1978). Which Media do University Teachers Actually Use? A Survey of the Use of Audio-Visual Media in Teaching at Two New Zealand Universities. British Journal of Educational Technology, 9(2), 149-160.

Terras, M. M., & Ramsay, J. (2012). The five central psychological challenges facing effective mobile learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(5), 820-832.

Thomas, P., Carswell, L., Price, B., & Petre, M. (1998). A holistic approach to supporting distance learning using the Internet: transformation, not translation. British Journal of Educational Technology, 29(2), 149-161.

Thornbury, R. (1979). Resource Organization in Secondary Schools: the report of an investigation. British Journal of Educational Technology, 10(2), 129-134.

Tidhar, C. (1973). Can Visual Reminders Increase Learning from Television? British Journal of Educational Technology, 4(2), 142-149.

Toetenel, L., & Rienties, B. (2016). Analysing 157 learning designs using learning analytic approaches as a means to evaluate the impact of pedagogical decision making. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(5), 981-992.

Tondeur, J., Aesaert, K., Pynoo, B., van Braak, J., Fraeyman, N., & Erstad, O. (2017). Developing a validated instrument to measure preservice teachers ICT competencies: Meeting the demands of the 21st century. British Journal of Educational Technology, 48(2), 462-472.

Trathen, C., & Sajeev, A. S. M. (1996). A protocol for computer mediated education across the Internet. British Journal of Educational Technology, 27(3), 204-213.

Turok, B. (1975). Telephone Conferencing for Teaching and Administration in the Open University. British Journal of Educational Technology, 6(3), 63-70.

Van Bruggen, J. (2005). Theory and practice of online learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 36(1), 111-112.

Van den Branden, J., & Lambert, J. (1999). Cultural issues related to transnational Open and Distance Learning in universities: a European problem? British Journal of Educational Technology, 30(3), 251-260.

Veletsianos, G., Collier, A., & Schneider, E. (2015). Digging deeper into learners experiences in MOOCs: Participation in social networks outside of MOOCs, notetaking and contexts surrounding content consumption. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(3, SI), 570-587.

Wall, K., Higgins, S., & Smith, H. (2005). ‘The visual helps me understand the complicated things: pupil views of teaching and learning with interactive whiteboards. British Journal of Educational Technology, 36(5), 851-867.

Warburton, S. (2009). Second Life in higher education: Assessing the potential for and the barriers to deploying virtual worlds in learning and teaching. British Journal of Educational Technology, 40(3), 414-426.

Weismayer, C., & Pezenka, I. (2017). Identifying emerging research fields: a longitudinal latent semantic keyword analysis. Scientometrics, 113(3), 1757-1785.

West, R., & Borup, J. (2014). An analysis of a decade of research in 10 instructional design and technology journals. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(4), 545-556.

Wheeler, P. S. (1980). The microwriter as an educational aid. British Journal of Educational Technology, 11(3), 160-169.

White, P. B. (1980). Educational technology research - towards the development of a new agenda. British Journal of Educational Technology, 11(3), 170-177.

Whitworth, D. E., & Wright, K. (2015). Online assessment of learning and engagement in university laboratory practicals. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(6), 1201-1213.

Wild, M., & Quinn, C. (1998). Implications of educational theory for the design of instructional multimedia. British Journal of Educational Technology, 29(1), 73-82.

Wilkes, J. (1977). Under-Utilization of Audio-Visual Aids: Some Comparative Evidence from History Teachers in Northern Ireland. British Journal of Educational Technology, 8(1), 27-33.

Williams, D., Coles, L., Wilson, K., Richardson, A., & Tuson, J. (2000). Teachers and ICT: current use and future needs. British Journal of Educational Technology, 31(4), 307-320.

Willis, N. E. (1990). Is educational technology delivering the goods? British Journal of Educational Technology, 21(1), 60-61.

Wood, R., & Ashfield, J. (2008). The use of the interactive whiteboard for creative teaching and learning in literacy and mathematics: a case study. British Journal of Educational Technology, 39(1), 84-96.

Yang, Y.-F., Yeh, H.-C., & Wong, W.-K. (2010). The influence of social interaction on meaning construction in a virtual community. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(2), 287-306.

Yildiz, R., & Atkins, M. (1996). The cognitive impact of multimedia simulations on 14 year old students. British Journal of Educational Technology, 27(2), 106-115.

Zawacki-Richter, O., Alturki, U., & Aldraiweesh, A. (2017). Review and Content Analysis of the International Review of Research in Open and Distance/Distributed Learning (2000-2015). The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(2).

Zawacki-Richter, O., & Latchem, C. (2018). Exploring four decades of research in Computers & Education. Computers & Education, 122, 136-152.

Zawacki-Richter, O., & Naidu, S. (2016). Mapping research trends from 35 years of publications in Distance Education. Distance Education, 37(3), 245-269.

Zhao, H., Sullivan, K. P. H., & Mellenius, I. (2014). Participation, interaction and social presence: An exploratory study of collaboration in online peer review groups. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(5), 807-819.

收稿日期:2019-06-04

定稿日期:2019-07-27

作者簡介:梅丽莎·邦德(Melissa Bond),德国奥尔登堡卡尔·冯·奥西茨基大学(Carl von Ossietzky Universit?t Oldenburg)教育与社会科学部开放教育研究中心副研究员,博士生;研究兴趣:以教育技术为媒介的学生学习投入、K-12翻转课堂、国际学术协作和学术出版。

奥拉夫·扎瓦克奇-里克特(Olaf Zawacki-Richter)博士,德国奥尔登堡卡尔·冯·奥西茨基大学教育与社会科学部开放教育研究中心教育技术教授。

马克·尼克尔斯(Mark Nichols)博士,撰写此文时任英国开放大学(Open University, UK)技术促进学习总监;BJET编委会委员。

译者简介:肖俊洪,汕头广播电视大学教授,Distance Education(Taylor & Francis)期刊副主编,System:An International Journal of Educational Technology and Applied Linguistics(Elsevier)期刊编委。https://orcid.org/0000-0002- 5316-2957

责任编辑 韩世梅

Laurillard, D., Kennedy, E., Charlton, P., Wild, J., & Dimakopoulos, D. (2018). Using technology to develop teachers as designers of TEL: Evaluating the learning designer. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(6), 1044-1058.

Leese, M. (2009). Out of class-out of mind? The use of a virtual learning environment to encourage student engagement in out of class activities. British Journal of Educational Technology, 40(1), 70-77.

Lewis, B. (1971a). Course Production at the Open University I: Some Basic Problems. British Journal of Educational Technology, 2(1), 4-13.

Lewis, B. (1971b). Course Production at the Open University III: Planning and Scheduling. British Journal of Educational Technology, 2(3), 189-204.

Lewis, L., Trushell, J., & Woods, P. (2005). Effects of ICT group work on interactions and social acceptance of a primary pupil with Aspergers Syndrome. British Journal of Educational Technology, 36(5), 739-755.

Leydesdorff, L. (1997). Why words and co-words cannot map the development of the sciences. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 48(5), 418-427.

Liesch, P. W., H?kanson, L., McGaughey, S. L., Middleton, S., & Cretchley, J. (2011). The evolution of the international business field: a scientometric investigation of articles published in its premier journal. Scientometrics, 88(1), 17-42.

Lin, J., & Lee, S. T. (2012). Mapping 12 Years of Communication Scholarship: Themes and Concepts in the Journal of Communication. In D. Hutchison, T. Kanade, J. Kittler, J. M. Kleinberg, F. Mattern, J. C. Mitchell, . . . G. Chowdhury (Eds.), Lecture Notes in Computer Science. The Outreach of Digital Libraries: A Globalized Resource Network (Vol. 7634, pp. 359-360). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Lynch, L., Fawcett, A. J., & Nicolson, R. I. (2000). Computer-assisted reading intervention in a secondary school: an evaluation study. British Journal of Educational Technology, 31(4), 333-348.

Madden, A., Ford, N., Miller, D., & Levy, P. (2005). Using the Internet in teaching: the views of practitioners (A survey of the views of secondary school teachers in Sheffield, UK). British Journal of Educational Technology, 36(2), 255-280.

Mansfield, R., & Nunan, E. (1978). Towards an Alternative Educational Technology. British Journal of Educational Technology, 9(3), 170-176.

Marín, V. I., Duart, J. M., Galvis, A. H., & Zawacki-Richter, O. (2018). Thematic analysis of the international journal of educational Technology in Higher Education (ETHE) between 2004 and 2017. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15(1), 685.

Marín, V. I., Zawacki-Richter, O., Pérez Garcías, A., & Salinas, J. (2017). Educational Technology trends in the Ibero-American world: 20 years of the Edutec-e journal. Edutec. Revista Electrónica De Tecnología Educativa. Advance online publication.

Marland, P. (1989). An approach to research on distance learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 20(3), 173-182.

Marriott, P. (2009). Students evaluation of the use of online summative assessment on an undergraduate financial accounting module. British Journal of Educational Technology, 40(2), 237-254.

Mason, R., Pegler, C., & Weller, M. (2004). E-portfolios: an assessment tool for online courses. British Journal of Educational Technology, 35(6), 717-727.

McCormick, R. (1985). Students Views on Study at the Radio and Television Universities in China: an investigation in one local centre. British Journal of Educational Technology, 16(2), 84-101.

McEvoy, J., & McConkey, R. (1991). Self-instructional videocourses - A cost effective approach to in-service training of teachers in special education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 22(3), 164-173.

McKenney, S., & Mor, Y. (2015). Supporting teachers in data-informed educational design. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(2, SI), 265-279.

Melton, R. F. (1990). Transforming text for distance learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 21(3), 183-195.

Menis, J. (1987). Teaching by computers-What the teacher thinks about it and some other reflections. British Journal of Educational Technology, 18(2), 96-102.

Min, R. (1994). Parallelism in open learning and working environments. British Journal of Educational Technology, 25(2), 108-112.

Mitra, S., & Rana, V. (2001). Children and the Internet: experiments with minimally invasive education in India. British Journal of Educational Technology, 32(2), 221-232.

Montgomery, A. P., Mousavi, A., Carbonaro, M., Hayward, D. V., & Dunn, W. (2017). Using learning analytics to explore self-regulated learning in flipped blended learning music teacher education. British Journal of Educational Technology.

Moore, D. M., Wilson, L., & Armistead, P. (1986). Media research - a graduate students primer. British Journal of Educational Technology, 17(3), 185-193.

Morgan, A., Taylor, E., & Gibbs, G. (1982). Variations in Students Approaches to Studying. British Journal of Educational Technology, 13(2), 107-113.

Moss, G. (1979). The Influence of an In‐Service Course in Educational Technology on the Attitudes of Teachers. British Journal of Educational Technology, 10(1), 69-80.

Mott, S., Ward, C., Miller, B., Price, J., & West, R. (2012). “British Journal of Educational Technology”, 2001-2010. Educational Technology, 52(6), 31-35.

Mukhopadhyay, M., & Parhar, M. (2001). Instructional design in multi-channel learning system. British Journal of Educational Technology, 32(5), 543-556.

Murphy, E. (2004). Recognising and promoting collaboration in an online asynchronous discussion. British Journal of Educational Technology, 35(4), 421-431.

Myll?ri, J., ?hlberg, M., & Dillon, P. (2010). The dynamics of an online knowledge building community: A 5-year longitudinal study. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(3), 365-387.

National Council for Educational Technology Training and Innovation Committee. (1971). Educational Technology and the Training of Teachers. British Journal of Educational Technology, 2(2), 99-110.

Newton, P. M. (2015). The learning styles myth is thriving in higher education. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1-5.

Newton, P. M., & Miah, M. (2017). Evidence-Based Higher Education - Is the Learning Styles ‘Myth Important? Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1-9.

Ngambi, D. (2013). Effective and ineffective uses of emerging technologies: Towards a transformative pedagogical model. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(4, SI), 652-661.

Nikolova, I., & Collis, B. (1998). Flexible learning and design of instruction. British Journal of Educational Technology, 29(1), 59-72.

Nix, I., & Wyllie, A. (2011). Exploring design features to enhance computer-based assessment: Learners' views on using a confidence-indicator tool and computer-based feedback. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42(1), 101-112.

Norris, N., Davies, R., & Beattie, C. (1990). Evaluating new technology - the case of the interactive video in schools (IVIS) program. British Journal of Educational Technology, 21(2), 84-94.

Nunez-Mir, G. C., Iannone, B. V., Pijanowski, B. C., Kong, N., & Fei, S. (2016). Automated content analysis: addressing the big literature challenge in ecology and evolution. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 7(11), 1262-1272.

Okwudishu, C. O., & Klasek, C. (1986). An analysis of the cost-effectiveness of educational radio in Nepal. British Journal of Educational Technology, 17(3), 173-185.

ONeill, S., Scott, M., & Conboy, K. (2011). A Delphi study on collaborative learning in distance education: The faculty perspective. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42(6), 939-949.

Ozdemir, S., & Kilic, E. (2007). Integrating information and communication technologies in the Turkish primary school system. British Journal of Educational Technology, 38(5), 907-916.

Pardo, A., & Siemens, G. (2014). Ethical and privacy principles for learning analytics. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(3), 438-450.

Pérez-Sanagustín, M., Nussbaum, M., Hilliger, I., Alario-Hoyos, C., Heller, R. S., Twining, P., & Tsai, C.-C. (2017). Research on ICT in K-12 schools - A review of experimental and survey-based studies in computers & education 2011 to 2015. Computers & Education, 104, A1-A15.

Persico, D., Pozzi, F., & Goodyear, P. (2018). Editorial: Teachers as designers of TEL interventions. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(6), 975-980.

Peruniak, G. S. (1984). The Seminar as an Instructional Strategy in Distance Education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 15(2), 107-124.

Perzylo, L. (1993). The application of multimedia CD-ROMS in schools. British Journal of Educational Technology, 24(3), 191-197.

Pimmer, C., Linxen, S., & Groehbiel, U. (2012). Facebook as a learning tool? A case study on the appropriation of social network sites from mobile phones in developing countries. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(5), 726-738.

Pitt, M. (1996). The use of electronic mail in undergraduate teaching. British Journal of Educational Technology, 27(1), 45-50.

Plowman, L. (1996). Narrative, linearity and interactivity: Malting sense of interactive multimedia. British Journal of Educational Technology, 27(2), 92-105.

Plowman, L., & Chambers, P. (1994). Working with the new generation of interactive media technologies in schools CD-I and CD-TV. British Journal of Educational Technology, 25(2), 125-134.

Prosser, M. T. (1984). Towards more effective evaluation studies of educational media. British Journal of Educational Technology, 15(1), 33-42.

Reid, F., & Champness, B. (1983). Wisconsin Educational Telephone Network: how to run educational teleconferencing successfully. British Journal of Educational Technology, 14(2), 85-102.

Riley, J. (1984a). An Explanation of Drafting Behaviours in the Production of Distance Education Materials. British Journal of Educational Technology, 15(3), 226-238.

Riley, J. (1984b). The problems of drafting distance education materials. British Journal of Educational Technology, 15(3), 192-204.

Riley, J. (1984c). The problems of revising drafts of distance education materials. British Journal of Educational Technology, 15(3), 205-226.

Ritzhaupt, A. D., Sessums, C. D., & Johnson, M. C. (2012). Where should educational technologists publish their research? An examination of peer-reviewed journals within the field of educational technology and factors influencing publication choice. Educational Technology, 52(6), 47-56.

Romiszowski, A. J. (1981). A New Look at Instructional Design. Part I. Learning: Restructuring Ones Concepts. British Journal of Educational Technology, 12(1), 19-48.

Romiszowski, A. J. (1982). A New Look at Instructional Design. Part II. Instruction: Integrating Ones Approach. British Journal of Educational Technology, 13(1), 15-55.

Rowntree, D. (1995). Teaching and learning online-a correspondence education for the 21st century. British Journal of Educational Technology, 26(3), 205-215.

Rushby, N. (2004). Editorial. British Journal of Educational Technology, 35(3), 261-262.

Rushby, N., & Seabrook, J. (2008). Understanding the past-illuminating the future. British Journal of Educational Technology, 39(2), 198-233.

Rushby, N. (2010). Editorial: topics in learning technologies. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(3), 343-348.

Rushby, N. (2011). Editorial: trends in learning technologies. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42(6), 885-888.

Rushby, N. (2012). Editorial: Where to publish, what to publish. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(4), 531-532.

Rushby, N. (2013). Editorial: Open Access. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(2), 179-182.

Salmon, G. (2009). The future for (second) life and learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 40(3), 526-538.

Schwier, R., Hill, J., Wager, W., & Spector, J. M. (2006). Where have we been and where are we going? Limiting and liberating forces in IDT. In M. Orey, J. McLendon, & R. Branch (Eds.), Educational Media and Technology Yearbook (pp. 75-96). Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

Scupham, J. (1970). Broadcasting and the Open University. British Journal of Educational Technology, 1(1). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.1970.tb00516.x

Selwyn, N., & Bullon, K. (2000). Primary school childrens use of ICT. British Journal of Educational Technology, 31(4), 321-332.

Selwyn, N., Potter, J., & Cranmer, S. (2009). Primary pupils use of information and communication technologies at school and home. British Journal of Educational Technology, 40(5), 919-932.

Shabajee, P., McBride, B., Steer, D., & Reynolds, D. (2006). A prototype Semantic Web-based digital content exchange for schools in Singapore. British Journal of Educational Technology, 37(3), 461-477.

Sharif, A., & Cho, S. (2015). 21st-Century Instructional Designers: Bridging the Perceptual Gaps between Identity, Practice, Impact and Professional Development. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 12(3), 72-85.

Shin, N. M., & Chan, J. K. Y. (2004). Direct and indirect effects of online learning on distance education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 35(3), 275-288.